Table of Contents

Background

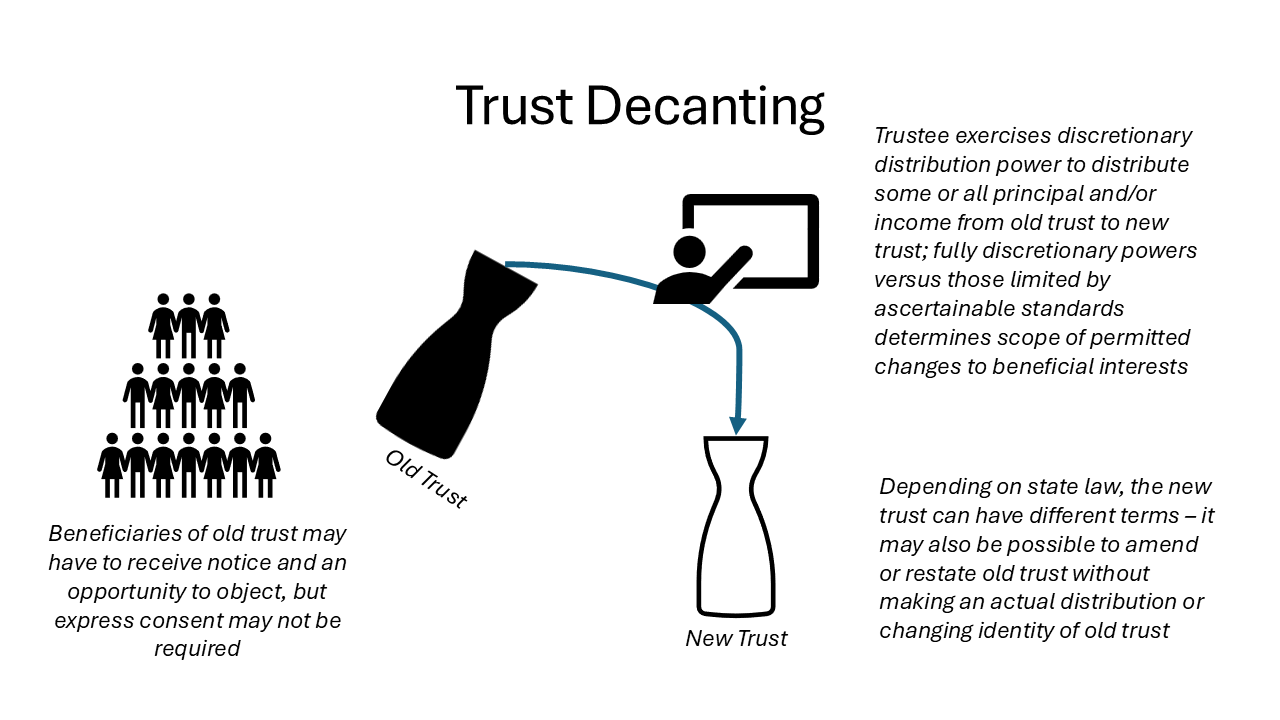

In recent years, the idea of decanting has gained popularity in estate planning. Simply put, much like old wine can be decanted into a new container, legal theories about trusts have evolved to suggest that trust assets can be similarly poured into a new or existing, but separate, trust as a function of a trustee’s discretionary distribution powers.

Of course, things are rarely this simple. A primary function of trusts is stability for long-term management and administration of trust assets, which can protect beneficiaries (and sometimes settlors) from taxes, creditor claims, and even themselves. However, these goals are contingent upon a trust being irrevocable. Traditionally, this was thought of as a rigidity of trust structures as set forth in a trust instrument. Irrevocability also has significance during a settlor’s life, by reflecting a permanence of transfers by a settlor to an inter vivos irrevocable trust (that cannot be taken back without at least equivalent exchange of value, and usually the consent of a trustee other than for a substitution power).

However, what constitutes the “gold standard” of planning today may not reflect the gold standard tomorrow. While death and taxes are often touted as certainties, changes to tax and other laws and regulations perhaps can be added to that list. Likewise, beneficiaries and family structures change and evolve over time. What makes sense when children of a wealth creator are in their young adult years may not make as much sense when they reach retirement age. Rigidity of a trust can, in some cases, become a detriment. Yet many beneficiaries and trustees have only a limited ability to act alone (such as through a power of appointment), or in concert to alter a trust especially if such an alteration violates a material purpose of a settlor in creating the trust to begin with. (On that note, even the definition of “material purpose” continues to evolve.)

Similarly, no two states’ trust laws are the same. Even for states that have adopted the Uniform Trust Code (UTC), two states’ versions of this model act can differ significantly. While administration in a settlor’s state of domicile may at least have initially made sense, the long-term view may show that beneficiaries of the trust can glean more benefits from administration of a trust in a different state. Questions even abound as to whether a trustee might even have a duty to consider the optimal trust jurisdiction based on the best interests of the beneficiaries.

While there are several possible tools for trustees and beneficiaries alike to address these issues, decanting has trended towards being the tool of choice due to its low friction (depending on the state), avoidance of court approval, and possibly avoidance of beneficiary consent (and in some cases, even notice). However, this administrative ease is not without its drawbacks. As we will find out, decanting is a trustee-driven decision which has the possibility of increasing the fiduciary risk to a trustee. This risk is exacerbated by the frequent practicality that the idea for decanting is not an original idea of the trustee, but may be suggested or even directed by a settlor or beneficiary (who themselves might be influenced by an outside party) – at its core raising issues of whose interests the trustee is serving.

Extension of Distribution Power

The foundation for decanting is the trustee’s discretionary distribution power. A traditional trust distribution is thought of as a direct transfer of cash or property from the trust to a beneficiary. However, the terms of the trust and (increasingly) state law recognize that this is not the only form of trust distribution. Generally, a trustee may also make distributions for the benefit of one or more trust beneficiaries – sometimes on an exclusive basis whereby distributions to one beneficiary do not have to be equal to distributions to another beneficiary. Such a distribution might include, for example, a direct payment of a beneficiary’s bills to the source. Another example might be the beneficiary’s rent-free use of trust property, such as a residence. Or, perhaps a trust could invest in a business started by the beneficiary in exchange for an equity interest.

Trust decanting started as the theory that a distribution for the benefit of a beneficiary could also extend to a distribution into another trust, new or existing, for that beneficiary. This theory initially found rooting in various Restatement approaches to trust distribution powers, and powers of appointment, whereby a holder of a power of appointment had the power to transfer property to a new or different trust. By equating a trustee’s discretionary distribution powers with powers of appointment, common law supposed that distribution to a new trust could be a natural extension of a trustee’s powers but subject to the trustee’s fiduciary duties (unlike a nonfiduciary power of appointment).

These fiduciary duties created, and continue to create, the guardrails for decanting. In a sense, they put a trustee in the seat of also being a settlor of a trust but without expressly being recognized as such (and without supplanting the consistent identity of the original settlor, which carries over to the new trust in many states). This means a trustee cannot reduce their fiduciary liability by a decanting. It also limits whether, and to what extent, a beneficiary’s (beneficial) interest in a trust can be reduced, eliminated, or diluted.

Scope of Decanting

States can vary drastically on the issue of whether decanting is permitted to begin with, and if so to what extent. The Uniform Law Commission has promulgated the Uniform Trust Decanting Act which has been adopted by some states, but this Uniform Act has not gained as much traction as the UTC or other model acts for trusts.

Decanting often explores one or more changes to trustees, trustee’s powers, classes of beneficiaries, distribution rights of beneficiaries, and even powers of appointment or invasion held by beneficiaries. An evolution of directed trust structures can allow fiduciary duties to be split between various trustee functions, but adoption of such a governance structure often requires decanting or modification of a trust (as will be discussed below). Changes in tax laws can also create incentives to update the structure and deemed tax ownership of a trust to, for example, “borrow” a beneficiary’s estate and GST tax exemptions through gross estate inclusion (directly or incidentally creating a step-up in basis for appreciated assets) or to create a grantor trust where one might not have previously existed. Finally, where a beneficiary’s circumstances change, traditional trust structures could create guaranteed distributions to a beneficiary when they are most vulnerable and an update to such structures can be valuable.

At its highest level, decanting works best in a situation where a trustee has a fully discretionary distribution power. This is perhaps the broadest distribution power, but it necessitates the appointment of an independent trustee to limit tax and creditor issues with respect to a beneficiary, the settlor (during life), or the trustee themselves. Such a power permits free decanting to a second trust in most states, even in a manner that removes beneficiaries or changes the structure of a beneficiary’s interest (including distribution rights, and even powers of appointment). Addition of beneficiaries may not always be possible, depending on the state, and even with a fully discretionary distribution power it may not be possible to reduce or eliminate a vested interest in a trust.

This fully discretionary distribution power is contrasted with a power that is limited by an ascertainable standard such as health, education, maintenance, support, and welfare. For trustees holding a discretionary distribution power subject to such a standard, they may have the power to decant but this power is often limited. In many states, this means a trustee can only decant in a manner that results in each beneficiary’s interest in the new trust being substantially similar to their interest in the old trust.

With respect to a trustee, a decanting often cannot decrease a trustee’s overall liability for breach of fiduciary duties. Likewise, many states limit or restrict a trustee’s use of decanting to increase compensation – at least without notice or consent of beneficiaries. But, decanting can be used to divide and reallocate fiduciary powers and duties in a directed trust structure to various trust advisors and protectors and, in the process, to limit a trustee’s duties with respect to functions for which they are so directed.

Decanting Issues and Alternatives

As noted above, states can vary on the treatment and availability of decanting. One area of variance is whether and to what extent a trust can override a state’s laws on decanting to increase a decanting power of a trustee. Many modern trusts include a decanting power, whether discretionary to a trustee or directed by a trust advisor or protector. Where decanting is not available, however, a change in situs may be solution. Likewise, depending on the tax consequences and trade-offs relating thereto (including fiduciary duties of a trustee), a sale of assets from one trust to another may be a possible workaround. A trust that is selling assets can even be a deemed income taxpayer of another trust for this purpose.

Of course, as noted above, one must be conscious of where the idea for decanting originates. A trustee who owes fiduciary duties to the beneficiaries – including duties of impartiality – may run into trouble for acting at the behest of a settlor or one particular beneficiary (including an advisor to either party) in carrying out a decanting. For a recent example of these pitfalls, see Paul Hood’s coverage in LISI Newsletter #3165 and follow-up materials.

Likewise, the tax and titling outcomes of decanting are not yet settled. In IRS Notice 2011-101, the Service requested comment on the possible income, gift, estate, and GST tax effects of decanting while also declaring this an area where PLRs will not be issued. In the meantime, a change in title from one trust to another trust – and corresponding change in taxpayer ID – was and continues to be recognized as an accounting and administrative nightmare for many trusts. While state decanting guidance often refers to a first or original trust, and a distribution therefrom to a second or receiving trust, many states (and the Uniform Act) permit “decanting” to be done in a manner that simply amends or restates the trust instrument of the original trust while not changing the identity of the original trust. While the prognosis remains unclear, this restatement process may prevent some tax issues. Nonetheless, one must be conscious especially of the tax issues inherent under IRC Sections 1001 and 2511, for example, when a beneficiary “exchanges” one form of beneficial interest for another in the decanting process. Likewise, decanting in a way that violates existing tax treatment (such as QTIP elections, or GST-exempt or GST-grandfathered status) may not be permitted by state law.

A common benefit of decanting is that it can be done without the express written consent of beneficiaries. This distinguishes decanting from nonjudicial modification, for example. Depending on the state, material purposes of a settlor may not limit decanting as much as they limit modifications. Lack of beneficiary consent may also keep a beneficiary from making a deemed gift, as a counterexample to recent cases and rulings such as CCA 202352018 and McDougall under which a beneficiary’s express consent to modification was a factor in determining that the beneficiary made a gift. However, many states require beneficiaries to receive notice of decanting, and an opportunity to request court review or approval within a certain period of time (such as 60 days). It is common practice to have beneficiaries waive this review period, but such an express waiver (or even the lapse of the review period itself) may be seen as a consent to modification for tax purposes.

Finally, decanting sometimes goes hand in hand with the division or consolidation of trusts. Many states and trusts grant a trustee the express authority to divide a trust (often for GST tax purposes), or to combine trusts. This express authority often requires notice to beneficiaries as well, and may require similarity (often substantial similarity) in a beneficiary’s interests and trusteeship of a trust. Decanting may provide a workaround where, for example, division or consolidation is not otherwise possible. For example, many states recognize that the decanting power can be used to divide a common trust for many current income beneficiaries into separate shares for each of them (which may not be possible under a traditional trust division power due to the differences in current and remainder beneficiaries thereafter).

Conclusion

While this article serves as a high-level overview of trust decanting, state-level review is an absolute necessity. An excellent guide can be found in Susan Bart’s state-by-state decanting summaries. It is important to also be wary of decanting as a universal solution, as it can sometimes be overprescribed in situations that lead to fiduciary liability or equitable relief.