Defining the Investment Partnership under IRC Section 721(b)

A look at when nonrecognition treatment may be denied

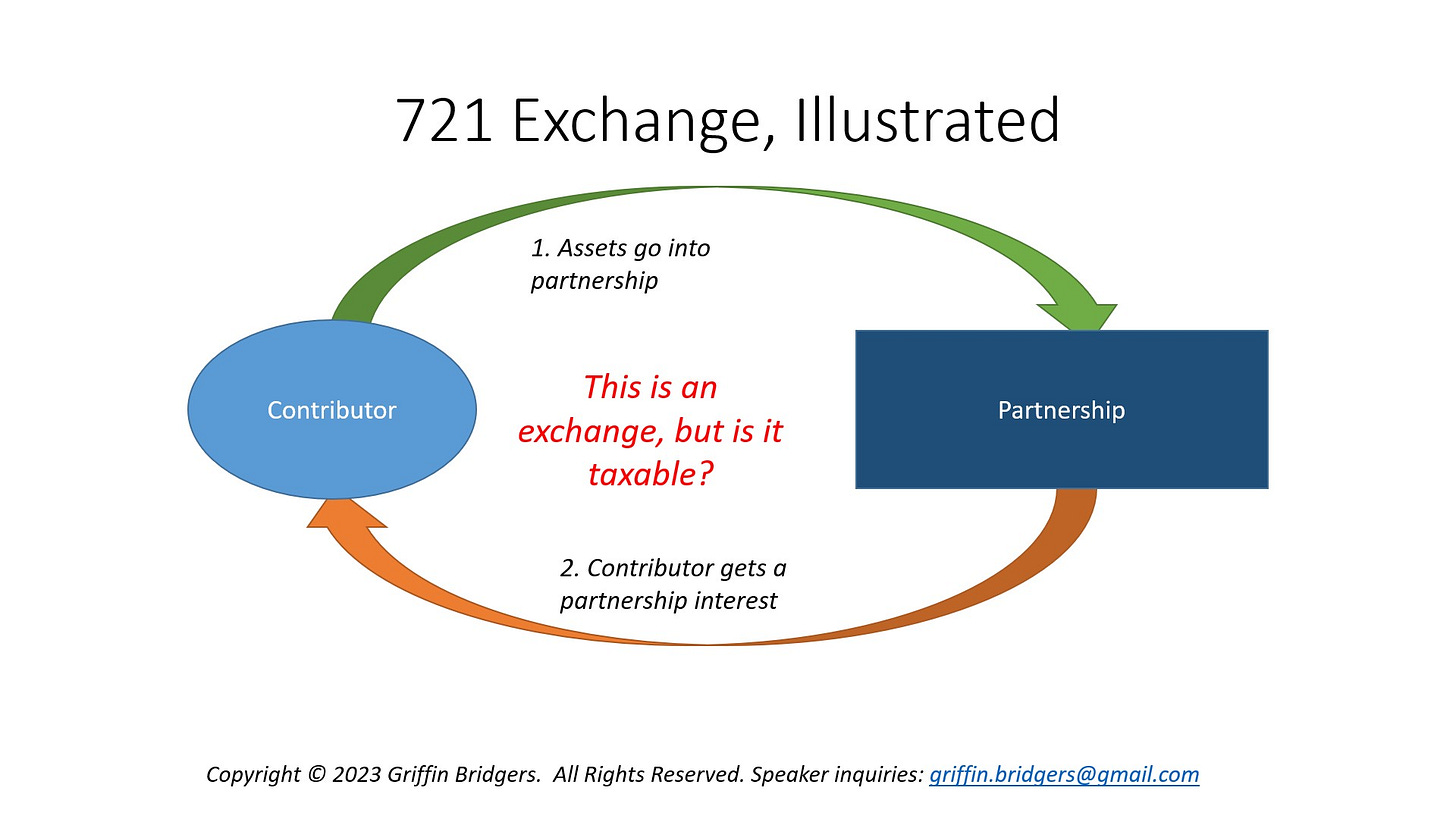

Contributions of property to a business entity, whether existing or newly-formed, in exchange for equity are commonly treated as nonrecognition transactions. In other words, the contributor’s contribution of appreciated property generally does not trigger recognition of gain. Instead, the contributor’s basis in the contributed assets is reflected in the basis of the equity interest created in the exchange.

In the estate planning context, which tends to rely on disregarded entities and tax partnerships, this nonrecognition treatment can be extremely important. Why? Because we often see pooling of appreciated assets in these forms of entities, whether between spouses or family members in multiple generations. Even where a disregarded entity is originally created, the addition of a new member, death of an existing member, or termination of a grantor trust can each trigger the technical creation of a tax partnership (resulting in the nonrecognition exchanges described above).

IRC Section 721(a) is where we see this nonrecognition treatment granted. This Code Section provides:

No gain or loss shall be recognized to a partnership or to any of its partners in the case of a contribution of property to the partnership in exchange for an interest in the partnership.

However, we cannot stop there. There is a companion provision - IRC Section 721(b) - which provides:

Subsection (a) shall not apply to gain realized on a transfer of property to a partnership which would be treated as an investment company (within the meaning of section 351) if the partnership were incorporated.

So, what does this mean? What is an investment company, and what does it have to do with partnerships? Before diving in, it helps to understand why we have these rules.

Diversification

As noted above, IRC Section 351 is the source of this investment company rule. While Section 351 is a bit more nuanced, it can have the same effect as 721 - nonrecognition treatment on the contribution of assets in exchange for corporate stock (with an added requirement of corporate control post-contribution, which we will not get into in this article).

This nonrecognition feature of both partnerships and corporations creates a unique opportunity for tax-deferred diversification of gains. As an individual, diversification of a concentrated portfolio would require the sale of positions, with accompanied gain recognition, followed by reinvestment in different securities (subject to the wash sale rule and other items of tax significance). But, as you can guess, there are limits to this diversification through entities reflected in the Internal Revenue Code, and the ultimate limit is found in this investment company rule.

It is important, however, to note that tax partnerships already have limits on the ability to shift gain from a contributor to other partners. So, even if gain can be deferred through multiple contributors pooling assets in reliance on IRC Section 721, they must also run the gauntlets of IRC Sections 704(c), 707, and 737 which have the general effect of defining each partner’s distribute share of partnership gain to include all pre-contribution gain reflected in their contributed assets, regardless of what their overall sharing ratios of partnership gain might be.

In other words, if you contribute appreciated assets and they are sold by the partnership, you will be taxed on the gain as if you still owned the assets regardless of your percent ownership of the partnership.

That being said, this gain treatment presupposes that gain on the contributed assets was deferred to begin with. Where diversification is too great, this is where the investment company rules kick in. We can generally find the principles of investment companies under IRC Section 351(e), and under Treas. Reg. 1.351-1(c). I will summarize some of the general rules here as apply to partnerships, but by no means is this a comprehensive analysis of the investment company rules with respect to corporations.

Hypothetical Incorporation

To test under Section 721(b), there must be a hypothetical incorporation of the partnership. In other words, you must analyze a hypothetical situation where, immediately after a contribution to a partnership, the the partnership converts to a C corporation for income tax purposes (whether by a check-the-box election, or by a state level conversion to a corporation).

Which brings me to the main point to remember here - outside of this hypothetical incorporation, we will be analyzing the transaction not from the perspective of the partnership but instead from the perspective of the contributor (i.e., the person who contributes assets in exchange for a partnership equity interest). After all, it is the contributor who may be forced to recognize gain on their partnership contribution - this rule does not force the partnership (or hypothetical corporation) to recognize or pass-through gain at the entity level.

Also, keep in mind that we are discussing a tax partnership, which for state law purposes could be organized as a partnership, LLC, or joint venture for example - hence why I will refer to “equity” interests and not necessarily “partnership” interests.

It is from this hypothetical incorporation that we must analyze whether the partnership, post-incorporation, would be treated as an investment company.

Investment Company, Defined

To arrive at the definition of “investment company,” there is one threshold inquiry that is often undertaken - are the partnership’s assets post-contribution, and post-(hypothetical) incorporation, comprised of more than 80% marketable securities held for investment (disregarding cash)? If so, you may have an investment company, but we cannot stop there. It is easy to fall into the assumption that simply creating this asset mix triggers the creation of an investment company, but more is required.

(Remember to separately analyze the “held for investment” requirement, as well as the definition of marketable [i.e., publicly-traded] securities. For purposes of this analysis, I will assume that both of these requirements are met, because to analyze these will take us down a rabbit hole from which there is no easy escape.)

Beyond this asset mix, we then have to look to whether there is direct, or indirect, diversification of the contributor’s interests through the contribution to the partnership. This inquiry is the core of the investment company analysis. To get there, Treas. Reg. 1.351-1(c) sets forth four exceptions which are actually fairly simple in their application. We will look at each in turn, and in each case we will be analyzing (with respect to one individual contributor) whether that contributor’s interests have been diversified, directly or indirectly.

One Contributor

If the hypothetical corporation only has one shareholder, there cannot be diversification for obvious reasons - true diversification is only achieved when there are multiple contributors.

Now, in the partnership context, this exception usually will not apply. To have a tax partnership, you usually need two separate and distinct taxpayers. If there is just one contributor for income tax purposes, you will not have a tax partnership, and you may not even have a state law partnership. While you could have an LLC, it would be a disregarded entity and would not be subject to IRC Section 721 unless or until an additional member (who is a separate and distinct taxpayer) is added. But, at that point, you would have to go through this analysis using a hypothetical contribution of the disregarded entity’s assets by the equity owners as both are then constituted.

All that being said, spouses can be separate and indistinct taxpayers for 721 purposes, even though they may file jointly. There are some exceptions, such as the contribution of community property (for which you can attain disregarded entity status for a dual-member partnership or LLC if, among other things, the spouses elect not to file a 1065), but beyond this narrow exception we will usually have a tax partnership where spouses contribute assets.

Which raises the question - can there be diversification between spouses? Could their contribution of joint assets trip up the nonrecognition treatment, especially were securities are involved? That takes us to our second exception.

Identical Assets

Where there are multiple contributors who each contribute identical assets, there is no diversification and thus no investment company.

Between spouses, you would often see this arise where there is joint ownership of an investment account or securities portfolio (whether by law or by titling). But, when spouses have separate, individually-owned securities portfolios or investments that are being pooled, could we have an issue? Maybe, but perhaps not as we will see below. First, however, we must look at the third exception.

Nonidentical Assets are Not Significant

When taken in the aggregate, if nonidentical assets are contributed, there will be no diversification if the nonidentical assets do not make up a significant portion of the partnership’s assets post-contribution.

While there is no bright line test for this, Example 1 of the Treasury Regulation uses a figure of ~2% where 2 contributors put in identical assets of $10,000 total value, and a third contributor puts in nonidentical assets worth $200. In this fact pattern, the $200 of nonidentical assets are deemed insignificant, and thus there is no diversification.

But, you must consider significance in the aggregate. In Example 2, there are 50 contributors each putting in $200, which does cross the threshold into significance and thus creates diversification with respect to a contributor putting in assets.

Contributed Assets are Already Diversified

If, when comparing the contributed assets or portfolio to all partnership assets, there is already diversification before the contribution, then there is no diversification. This seems counterintuitive, but it will make sense when we consider its application. The rule on nonrecognition of gain is designed to prevent diversification of highly-concentrated securities positions. So, for example, if one contributor just put in Apple stock, and the other just put in Amazon stock, neither portfolio pre-contribution could be considered to be diversified, but there would be diversification post-contribution.

So, if we look to the most concentrated and five most concentrated positions, and compare those to the total post-contribution values of partnership assets, we may avoid diversification so long as the contributed positions do not cross a certain value threshold.

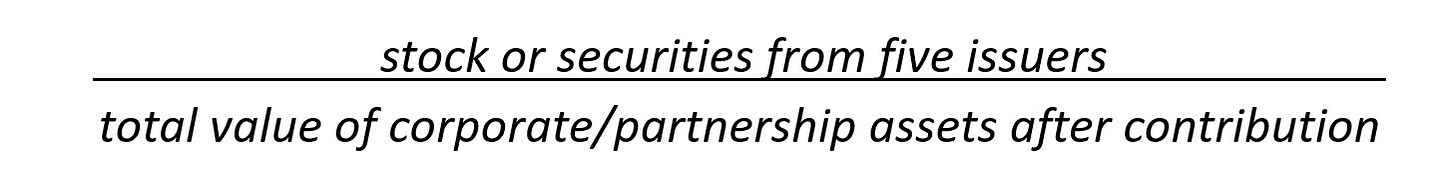

To get there, we will use a fraction in two tests, the numerator of which will look at the values of largest and five largest contributed positions, respectively, and the denominator of which will look at the value all partnership assets post-contribution, with some exceptions below.

Here is a quick snapshot of our fractions.

For the single-issuer test, we will use the following fraction:

For the five-issuer test, we will use the following fraction:

In each case, we are comparing the value of the one or five most concentrated positions to the total partnership value. But, the thresholds we will use are 25% and 50%, respectively. So, after the contribution, so long as no more than 25% of the partnership’s assets are comprised (by value) of the largest position (by value) in the portfolio contributed by the individual contributor, there will be no diversification. Assuming this test is passed, then so long as no more than 50% of the partnership’s assets are comprised (by value) of the five largest positions (by value) in the portfolio contributed by the individual contributor, there will be no diversification.

These tests are derived from IRC Section 368(a)(2)(F), which generally analyzes whether a merger of investment companies would be grant nonrecognition treatment to the shareholders of each investment company on the exchange of equity of one investment company for the other.

The general outcome here is that the more diversified a contributed portfolio is to begin with, the less the chance there is “diversification” of the contributor’s interests for purposes of IRC Sections 351 and 721.

Exceptions

In reviewing these fractions, there are a couple of exceptions of note.

For one, cash is excluded from both the numerator and denominator. Why? Because to recognize cash would allow a contributor to stuff cash into the partnership for purposes of passing these 25% and 50% tests.

On this note, government securities are excluded from the numerator, and not the denominator, except to the extent they are added to the partnership (or portfolio) for purposes of passing the 25% and 50% tests. So, while this rule helps those with portfolios that already have government securities, it does not help those who acquire government securities (or those who contribute them) solely for purposes of avoiding “diversification” of their interests.

Conclusion

While this is not a complete analysis, it hopefully gives a framework to analyze IRC Section 721(b) in a meaningful way, especially for family limited partnerships and family LLCs. While there was a lot thrown at you in this article, the key takeaway is that simply having >80% securities in the partnership is not enough to case gain recognition on a contribution to a partnership. We must also determine whether, on a per-contributor basis, there is direct or indirect diversification using the 25% and 50% tests above (assuming that the contributed assets are not identical, or that nonidentical assets are not significant).

So, in the grand scheme of things, surviving this test may be easier than anticipated at first glance. But, remember the trickle-down effects on the partnership and the contributor. If gain is recognized by the contributor, then this will increase the partnership’s basis in the assets, while also avoiding the application of IRC Sections 704(c), 707, and 737 to the (now-eliminated) pre-contribution gain. These Code Sections can only apply if IRC Section 721(b) does not apply to begin with.