Table of Contents

Background

So far in the series on grantor trusts, we have been covering ways to affirmatively and intentionally create grantor trusts – whether with respect to a grantor or contributor to the trust, or with respect to a beneficiary if a grantor or contributor is not the deemed income tax owner of the same portion of the trust.

At the time of publishing this article, the House is on the verge of voting on Trump’s tax legislation. Such legislation may have the effect of enhancing certain benefits available to both individuals and trusts, such as the gain exclusion for qualified small business stock (QSBS) under IRC Section 1202 and the qualified business income (QBI) deduction under IRC Section 199A. There is a catch, however, that is not new to tax law – these benefits at the trust level may be lost if the trust is a grantor trust. At the same time, there are some benefits that are denied to (nongrantor) trusts but may be available for a grantor trust, such as expensing deductions under IRC Section 179.

Trusts are often drafted with an eye toward avoiding retained interests for estate tax purposes under IRC Sections 2035-2038. But, it may also become increasingly important to draft trusts that avoid retained interests for grantor trust purposes – especially if the goal is availing the trust of certain income tax benefits and exclusions that are multiplied when the trust is a separate and independent taxpayer. Division of a trust into separate shares may also become a vital consideration, but this may also run headlong into the trust aggregation rules of IRC Section 643(f).

In the coming articles, we will cover some ways where grantor trust status can be accidentally created. For the time being, it is important to note that the powers we have covered so far – such as the substitution power under IRC Section 675(4)(C), and the power to revoke (or revest) under IRC Section 676 – usually require intentional drafting or selection of the clauses necessary to create this outcome. Where these types of clauses are omitted, the lack of intentionality with respect to other grantor trust powers can be exacerbated by the spousal attribution rules, or perhaps saved when there is an adverse party holding or sharing certain powers.

Perhaps a natural segue and starting point is found in IRC Section 674, which focuses on retained control of the beneficiary enjoyment of a trust.

IRC Section 674, in a Nutshell

One of the most confusing grantor trust provisions, perhaps because of its broad initial reach contrasted with the layering of several express exceptions, is found in IRC Section 674. This Code Section, starting out in Subsection (a), states:

The grantor shall be treated as the owner of any portion of a trust in respect of which the beneficial enjoyment of the corpus or the income therefrom is subject to a power of disposition, exercisable by the grantor or a nonadverse party, or both, without the approval or consent of any adverse party.

This is one of those Code Sections for which reliance on the relevant Treasury Regulations is also recommended for added context. Reading through 674(a), we stumble upon what could logically be considered the fist requirement for this Code Section to occur – a “power of disposition.” Treasury Regulation Section 1.674(a)-1(a) clarifies that this term generally includes “a power, beyond specified limits, to dispose of the beneficial enjoyment of the income or corpus, whether the power is a fiduciary power, a power of appointment, or any other power.” However, we cannot stop there. Although there seems to be a qualifier of “beyond specific limits,” this Regulation goes on to provide that 674(a) is presumed (in “general terms”) to apply “in every case in which [the grantor] or a nonadverse party can affect the beneficial enjoyment of a portion of a trust.”

In other words, this can seemingly include every single power of the grantor under the sun that can potentially affect the beneficial enjoyment of the trust. In addition, it can extend to powers of the grantor’s spouse that satisfy the spousal attribution rules of IRC Section 672(e).

There is something even more nefarious found in IRC Section 674(a), quoted above. The aforementioned powers of disposition can create a grantor trust if held by “the grantor or a nonadverse party, or both.” Does this mean that any power of disposition held solely by a trustee that is completely nonadverse – which seemingly would be a prescription for safety from the grantor trust rules – falls within this broad provision? Does it perhaps mean that we must have an adverse party serve as sole trustee?

This is where the broad exceptions of IRC Sections 674(b)-(d) come into play.

Introduction to the 674 Exceptions

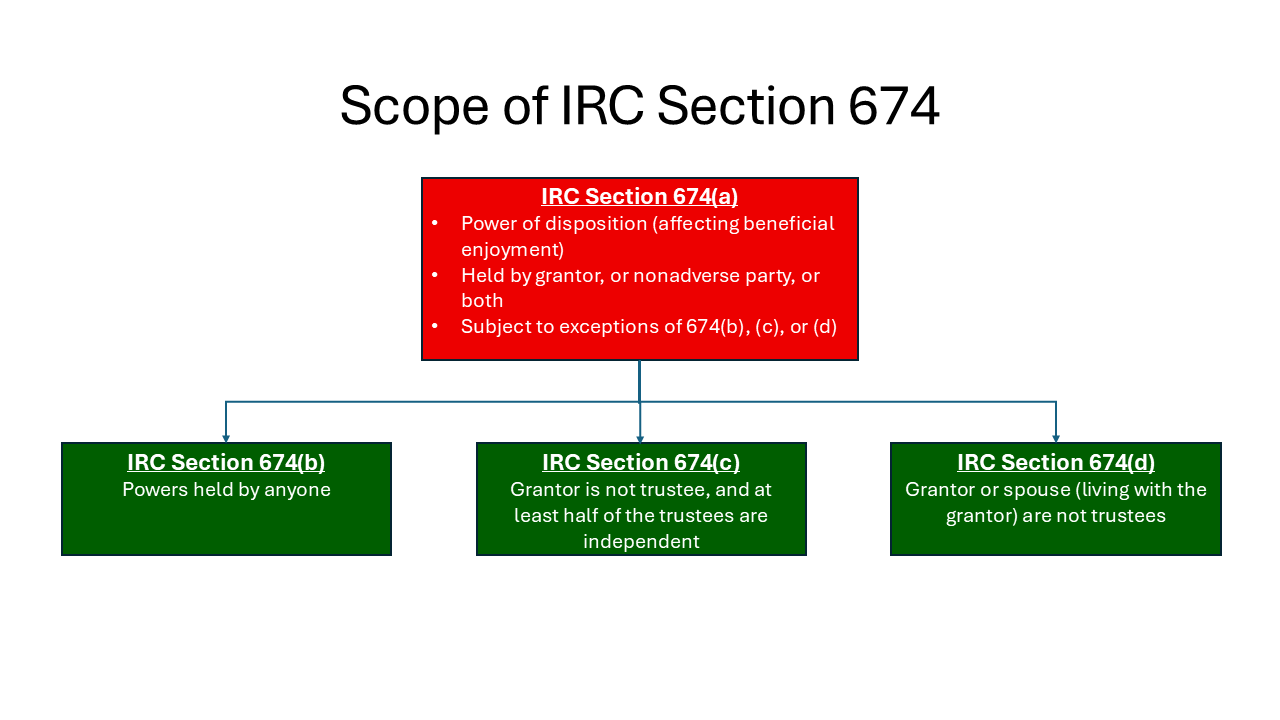

There are three categories of exceptions to the very broad rules IRC Section 674(a), set forth in IRC Sections 674(b), 674(c), and 674(d), respectively. Again, Treasury Regulation Section 1.674(a)-1(a) does a great job of summing up these categories of exceptions as follows:

Section 674(b) describes powers which are excepted regardless of who holds them. Section 674(c) describes additional powers of trustees which are excepted if at least half the trustees are independent, and if the grantor is not a trustee. Section 674(d) describes a further power which is excepted if it is held by trustees other than the grantor or his spouse (if living with the grantor).

So, all is not lost. The exceptions to the broad rule of 674(a), as we will discover, are quite broad and can help us avoid unintentional grantor trust status in a variety of situations. Nonetheless, ignorance of these exceptions is not recommended. While boilerplate language in a trust may prevent 674(a) from applying, the choice(s) of trustees and beneficiaries can also be a significant factor in determining whether and to what extent an exception to 674(a) is applicable.

To sum up, this image provides a quick overview of the exceptions – which we will expand upon in upcoming articles:`

Key Takeaways

As transfer tax exemptions have increased, the utility of estate and gift tax planning has been de-emphasized in favor of income tax planning (including income tax basis planning). Nonetheless, there is some overlap that will become important – a myopic view of income tax while eschewing transfer tax, and vice versa, is a fool’s errand when it comes to trust tax planning. For example, if one were to move QSBS stock into one or more nongrantor trusts, this could use some gift tax lifetime exclusion (requiring a valuation, a gift tax return, and adequate disclosure of the value of the stock). But, the alternative – creation of an incomplete gift trust – would potentially invoke IRC Section 674(a) due to the retained dominion or control required of the grantor in order to create an incomplete gift. This could be a potential $15,000,000 mistake (or more) based on QSBS reform.

Given the broad reach of IRC Section 674(a), it is safe to assume that many (if not all) trustee powers, powers of appointment, and even state-law powers could fall into its trap if they in any way, shape, or form affect the beneficial enjoyment of trust income or principal. This could include not just a trustee’s discretionary distribution powers or a (nonadverse) party’s power of appointment, but could also extend to state law powers such as a power of disclaimer by a trustee or even statutory fiduciary powers. Even where it is “assumed” that an intentional and releasable power, such as a power of substitution, is the sole mechanism of grantor trust status, prudent planning means ensuring that grantor trust status can truly be turned “off” if this is a goal.

Avoiding these risks involves navigation of the three categories of exceptions to IRC Section 674(a), which will be covered in upcoming articles.