When it comes to the estate tax return, IRS Form 706, there is a lot of confusion as to the mechanics of filing the return in situations where the filing is not required. Typically, we see three such scenarios – portability elections, QTIP elections, and allocation of GST exemption at death. Each of these scenarios may be related, and while it is possible that the 706 filing would be primarily driven by one scenario, it is possible that one or two others could apply.

Against this backdrop, this article focuses on the second scenario – the QTIP election – and how it can be made if there is no requirement to file Form 706. But, before we get started, it is helpful to break down the basic issue surrounding an “elective” 706 filing.

Elective 706 Filings

IRC Section 6018 lists the requirements for the filing of an estate tax return. Generally, the estate tax return must be filed if the decedent’s gross estate exceeds the positive difference between the basic exclusion amount (currently $12,920,000), and the decedent’s adjusted taxable gifts (if any). Notably, any deceased spousal unused exclusion amount preserved for the decedent by a previously deceased spouse does not increase this filing threshold. It also does not matter if deductions (including the marital and charitable deductions) zero out the estate tax liability – an estate tax return is still required where the gross estate crosses this threshold.

For nonresidents, this same rule applies, with three changes: (1) the filing threshold is reduced to $60,000, (2) the only assets counted in the gross estate are U.S. assets, as further defined in IRC Sections 2103-2105, and (3) adjusted taxable gifts are determined with the special rules of IRC Sections 2501(a)(2) (exempting transfers of intangible property) and 2511 (exempting non-U.S. property, but excluding stock and debt instruments of a U.S. company from the intangibles exception).

Against this backdrop, we have to consider the general QTIP requirements, found in IRC Section 2056(b)(7) (in particular 2056(b)(7)(B)(v). The application of the marital deduction to QTIP property requires, amongst other things, an election by the executor on the “return of tax imposed by [IRC] section 2001” (i.e., the Form 706).

So, in this regard, what happens when no estate tax return is required, but nonetheless we wish to make a QTIP election?

The QTIP Election, Then and Now

Part of the lack of guidance in this area stems from the need to borrow guidance from other areas – namely the portability election, which allows the preservation of the deceased spousal unused exclusion amount (the “DSUE”).

Prior to the enactment of portability at the end of 2010, it was possible for the estate tax applicable credit of the first spouse to die (in a married couple) to be lost if, for example, transfers overqualified for the marital deduction through a QTIP election or otherwise. Since QTIP property is included in the surviving spouse’s gross estate under IRC Section 2044, this could also unnecessarily increase the overall estate tax due on a married couple’s combined estate at the survivor’s death.

In response, Rev. Proc. 2001-38 created a procedure for the surviving spouse to disregard, or void, a prior QTIP election to the extent it was unnecessary. In other words, the scope of the QTIP election could be reduced to the minimum amount necessary to reduce the estate tax of the first spouse to die to zero. Many practitioners have incompletely cited this Revenue Procedure for the proposition that a QTIP election pre-portability could not exceed the amount necessary to zero out estate tax, but that is not true – this was still a possibility. However, it would have been folly to do so.

But, after the advent of the portability election, the issues of overtaxation at the survivor’s death and the loss of the applicable credit of the first spouse to die went away (assuming a portability election was, indeed, made). So, Rev. Proc. 2016-49 updated the guidance of Rev. Proc. 2001-38, to take away the surviving spouse’s option to disregard the QTIP election if a portability election was made by the estate of the first spouse to die. The effect was to no longer treat as void (at the election of the surviving spouse) a QTIP election in excess of the amount needed to zero out estate tax if the portability election was made, even if the DSUE preserved was zero (which ironically does not solve the problem in the case of zero DSUE, but I digress).

Long story short, the only reason we even have the question of an elective 706 for QTIP election purposes owes its existence to the portability election, and Rev. Proc. 2016-49. Prior to portability, the only need for a QTIP election was in cases where the gross estate (reduced by adjusted taxable gifts) exceeded the applicable exclusion amount. So, up until January 1, 2011 (the date portability became effective), usually every return on which a QTIP election was made was required to be filed, regardless of the QTIP election.

The Elective QTIP Return

So, the typical scenarios in which we can have a 706 that is not required to be filed, but upon which a QTIP election is made, now arise where the decedent’s gross estate (minus adjusted taxable gifts) is less than their basic exclusion amount, and/or where a portability election will be made. The two are not necessarily mutually exclusive, as the increase in QTIP elected assets increases the DSUE (and vice versa).

I will cover the portability election, and strategies relating thereto, in a separate article (see my current ongoing video series on YouTube). But, while the elective QTIP 706 does not necessarily require a portability election, it may be folly not to make such election because the elective QTIP 706 will only come up in scenarios where some of the decedent’s basic exclusion amount would be lost without the election. In other words, this QTIP election is “unnecessary” for any purpose other than preservation of DSUE, because it actually creates DSUE.

Prior to portability, there was no abbreviated method to prepare an estate tax return – the general requirements of the Form 706 instructions, along with accepted principles of adequate disclosure, had to be followed. This included the reporting of all assets in the gross estate, and their fair market value (either at date of death or, if elected, the alternate valuation date under IRC Section 2032). It is only since the enactment of portability that we have seen an abbreviated procedure for the preparation of an elective 706 for purposes of making the portability election, under Treas. Reg. 20.2010-2(a)(7)(ii), which in particular allows values to be estimated for assets reported on the return. While this may be a small administrative relief from a compliance perspective, it is notable for the reduction of the economic and administrative burden of appraising property.

(Again, I will discuss this valuation rule in a separate installment of this series on elective returns).

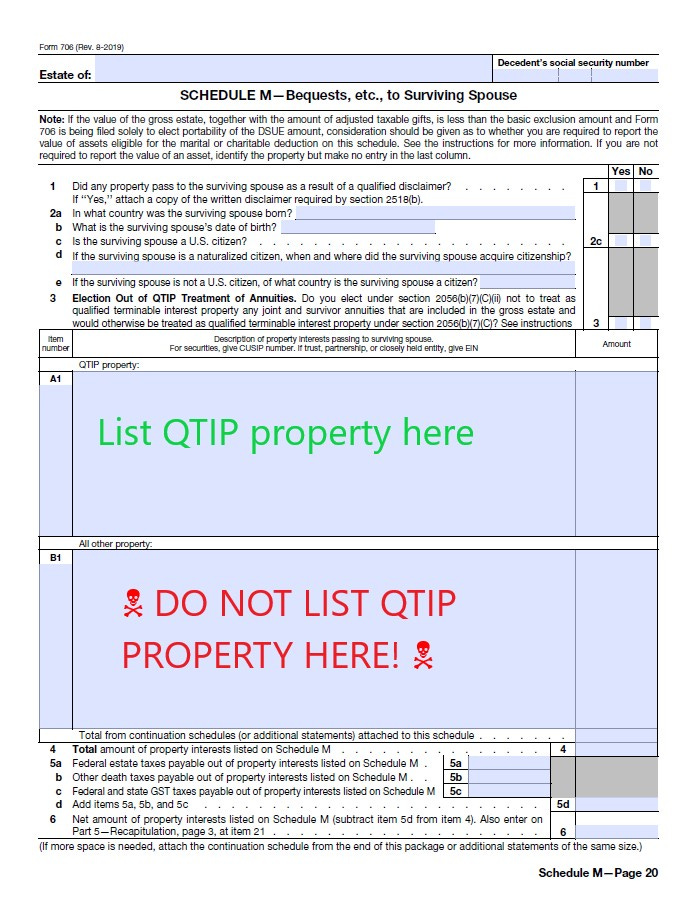

But, what we have not seen is an abbreviated procedure for preparing a 706 to make the QTIP election. While I am getting ahead of myself a bit, the QTIP election is made by listing QTIP property that will be subject to the election on the first entry box of Schedule M. (See my article, here, for more on this Schedule). It would seem intuitive for there to be a procedure whereby, for example, you could simply complete the basic info on Part 1 of the Form 706 coupled with Schedule M. Unfortunately, we do not have this type of procedure. Instead, it appears that we would have to piggyback off of the principles for a portability return.

Return Mechanics and Strategy

We will discuss portability return mechanics a bit more in a later article, but for the time being it is helpful to look to the technical requirements and timing. As noted in Treas. Reg. 20.2056(b)-7(b)(4), there is little guidance for the QTIP election itself outside of the requirement that the return required under IRC Section 2001 be filed. The election, once made, is irrevocable unless the filing deadline has not passed (in which case an amended return can be filed which revokes or modifies the prior QTIP election).

To expand on this, we often think of the election as being two-pronged. Much like Hamlet’s soliloquy ponders, “To be, or not to be….,” we often examine QTIP property from the decision to elect, or not to elect. But, when we refer to the election under the Code and Regulations, the wording applies only to an affirmative election (i.e., the decision to treat property as passing to a surviving spouse and thus qualifying for the estate tax marital deduction). Thus, when the election is referred to as irrevocable, this is the affirmative election which is applied on an asset-by-asset basis (with the ability to apply to fractions of assets).

However, to get granular, you cannot later amend or modify a QTIP election (before the 706 due date) to add other gross estate property that was not the subject of the prior QTIP election. As noted in Treas. Reg. 20.2056(b)-7(b)(4)(ii):

If an executor appointed under local law has made an election on the return of tax imposed by section 2001 (or section 2101) with respect to one or more properties, no subsequent election may be made with respect to other properties included in the gross estate after the return of tax imposed by section 2001 is filed.

So, the power to amend, revoke or modify seems to only permit the retraction of a QTIP election, and not an expansion to additional property or substitution of other property. This regulation is not clear, however, on whether this prohibition would extend to fractional interests in property to which the QTIP election is applied. In other words, is it possible that a later amended return could expand the QTIP election to a non-elected fraction of property, if only a portion of the property had been subject to the prior QTIP election?

Against this backdrop, one must think from the perspective of accuracy in value reporting. Much of the burden of preparing an estate tax return stems from the accurate reporting of value. However, the value as finally determined for estate tax purposes also determines the income tax basis of property (see IRC Section 1014(b)(9)). So, at least for accuracy of income tax reporting for the sale or exchange of QTIP assets, it would appear to be in the taxpayer’s best interest to accurately report the value of assets.

While lackadaisical reporting is often seen as harmless with respect to QTIP property (due to the lack of estate tax being immediately generated, and the coupling of understatement penalties to the tax due), such an attitude may generate an underpayment or overpayment of income tax on the part of the QTIP trustee that moves in reverse from the potential estate tax value. What do I mean? Well, if you understate the estate tax value, this reduces the basis, which could lead to an overpayment of income tax (for which there is no income tax penalty). On the other hand, while overstatement of value leads to no estate tax (due to the QTIP election) and no corresponding penalty, this could generate an understatement of income tax on the sale of the asset (due to the basis being too high).

Thus, even if the executor is represented by counsel who prepares the elective QTIP 706, it may be helpful for the QTIP trustee to be independently represented for purposes of reviewing the 706. There could be conflicting fiduciary duties with respect to the estate vs. income tax effects, and the trustee could be in breach of their duties if there is an overpayment or underpayment of income tax on the sale of a QTIP-elected asset due to faulty value reporting.

Jumping back to timeliness, however, this same issue of a lack of payment of estate tax (at the first spouse’s death) on the QTIP property often creates the belief that the QTIP election has no deadline. After all, if the penalty for late filing is based on the tax due, there can be no penalty on zero estate tax. Additionally, Treas. Reg. 20.2056(b)-7(b)(4)(i) seems to contemplate that the QTIP election would be respected on a late-filed return, with the only cost being the inability to later amend, revoke or modify the election.

But, as noted above, elective QTIP 706 filings would logically be accompanied by a portability election. The new deadline for portability returns is 5 years under Rev. Proc. 2022-32. So, the cost of delaying an elective QTIP 706 may not be the loss of the QTIP election, but may instead be the ancillary loss of the portability election. After all, as noted above, the two move in reaction to each other – the QTIP election increases the DSUE that can be preserved under a portability election, and vice versa.

Additionally, for QTIP-elected assets for which a portability election is also made, the executor gains the authority to estimate asset values under Treas. Reg. 20.2010-2(a)(7)(ii) – this is another benefit that is lost if the elective QTIP 706 is filed more than 5 years after the decedent’s date of death.

So, to conclude:

· Unsubstantiated values may not lead to understatement penalties for estate tax, but could lead to overpayment or underpayment of income tax if and when a QTIP-elected asset is sold.

· If a portability election is made, as we will later examine in the portability article, the special rule of Treas. Reg. 20.2010-2(a)(7)(ii) could allow the executor to estimate values for QTIP property, but this would then not establish the basis for property.

· There seems to be no deadline for a QTIP election, but since an elective QTIP 706 is usually coupled with an elective portability return, a delay beyond 5 years could cause a loss of the DSUE and a loss of the authority to estimate asset values.

I will discuss the estimation of value a bit more in the portability article, but for the time being, it may be helpful to give a second look to the Treas. Reg. 20.2010-2(a)(7)(ii) in an elective QTIP 706. The catch, however, is the inability to establish basis for QTIP-elected assets.

More on Completion

What this leaves is little difference between a required 706, and an elective QTIP 706. You still need to go through the exercise of reporting all property included in the decedent’s gross estate, at the appropriate valuation, on the appropriate schedule, with enough information to adequately disclose and identify each asset. The only possible abbreviated procedure would be an estimation of value of QTIP property where portability is to be elected.

Ultimately, as noted above, Schedule M becomes the location of QTIP property. The election is made by listing the property on the top portion of Schedule M, with each description and value being derived from its corresponding listing on the other Schedules (A-I). The following illustration, from my previous article on QTIP elections, shows where to report QTIP property:

But, in addition to this Schedule, be sure to complete Part 6 of the 706 if portability will be elected.

Since the elective QTIP 706 is not required under IRC Section 6018, an added benefit is that the basis consistency rules of IRC Section 1014(f) do not apply. Therefore, IRC Section 6035 does not apply, meaning Form 8971 does not have to be filed. Regardless, the trustee of the QTIP trust must be conscious of the basis reporting as noted above.

Conclusion

Perhaps, with time, Treasury will provide an abbreviated QTIP election procedure, but this is not on their priority list. For the time being, my hope is that this provides you with the information needed to advise your clients on elective QTIP 706 filings.

Stay tuned for guidance on other elective 706 filings – portability, and GST exemption allocations on Schedule R.