Table of Contents

Intro

Many of us are called to review and/or draft estate planning documents as part of our job. With experience, you gain the realization that even seemingly innocuous terms and structures in documents can be seized upon by an overly zealous fiduciary or beneficiary. When I see these differences come up, I like to file them away as another box to check.

A recent case from the Michigan Court of Appeals, Hords v. Chapman (In re Larry S. Berman Revocable Living Trust), decided on February 1, 2024, brought another important drafting point to light.

Background

Mr. Berman was the settlor of a revocable trust. After his death in 2014, at issue was the division of the trust. (While not a focus of this case, I find it important to note that even with a revocable trust there was a protracted administration of Mr. Berman’s trust and estate. The trustee was waiting for an estate tax closing letter. So, while revocable trusts are nice, they do not always streamline administration or avoid disputes.)

Mr. Berman had three children, all of whom survived him. But, while the trustee was waiting for the estate tax closing letter, one of Mr. Berman’s children died in 2021 leaving three children of their own (Mr. Berman’s grandchildren). The trust included the usual language about division of assets (after payment of expenses and taxes) into shares for children and descendants, per stirpes. But, the dispute was about whether the shares for Mr. Berman’s grandchildren, as takers representing their deceased parent, were to be distributed outright or in trust.

Common Distribution Structures

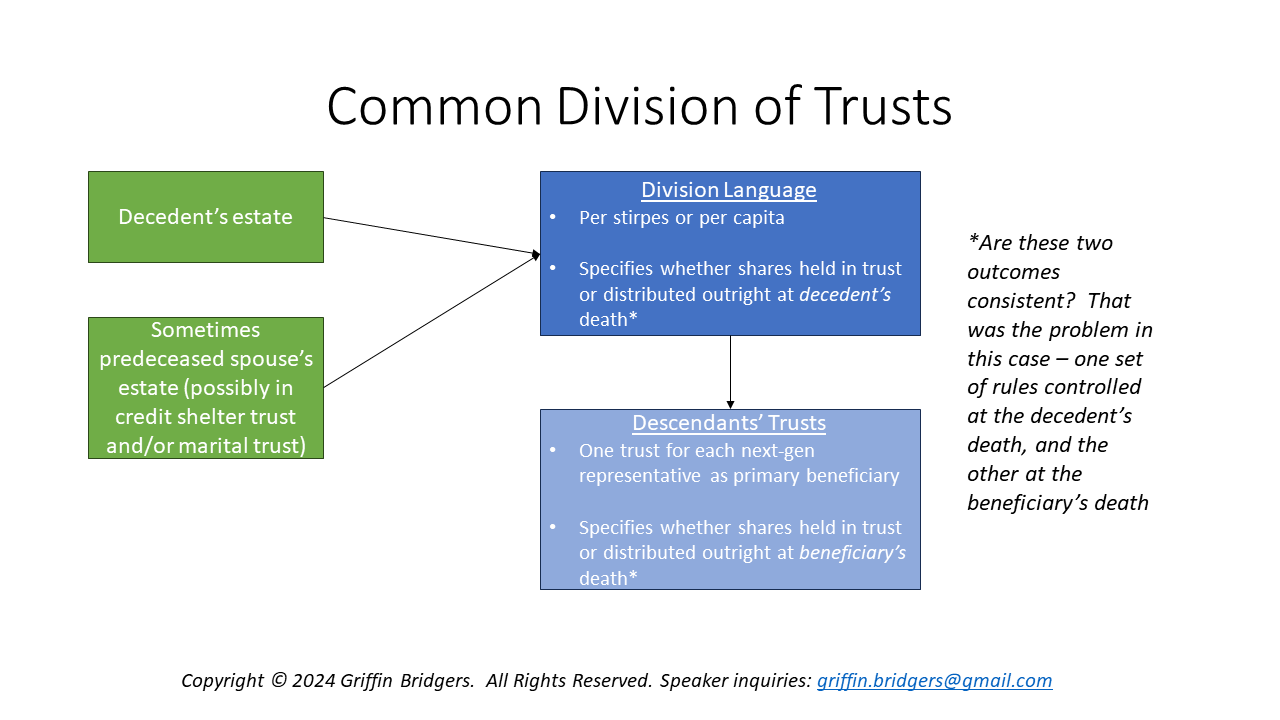

Many wills and trusts contain language that, in effect, creates a division of remaining trust assets per stirpes or by representation. In effect, one share is created for each child who either (1) survives the decedent, or (2) predeceases the decedent but leaves descendants living at the time of decedent’s death. Sometimes, a division per capita can be used, but its outcome usually only changes things if multiple family units have representation in no higher than the third generation at the time of division.

Like with estate tax valuation, this generational determination of takers is usually determined immediately at the time of the decedent’s death, but sometimes is subject to survivorship requirements stated elsewhere in the document (such as 30 days) or under state law governing simultaneous death (often requiring beneficiaries to survive a decedent by 120 hours).

But, what is also important is the determination of how each per stirpital share created for a descendant is to be administered. Long ago, these shares were often distributed outright. But, the trend over several years (or decades, for that matter) has been a shift to require per stirpital shares to be held in trusts for descendants. These shares may last for the lifetime of at least the next generation after the decedent, and sometimes may continue for multiple generations - possibly even to the end of the applicable perpetuities period.

The initial division, however, is not always instructive. One must also consider what happens at the death of a descendant whose share is held in trust. Sometimes, they have a power of appointment over their trust. Whether or not a power of appointment is granted, takers in default are usually named. Again, we often have a per stirpes or per capita distribution among the descendants of the (now-deceased) beneficiary of the trust. If the deceased beneficiary has no descendants at that time, their share may instead go to the settlor’s descendants, per stirpes or per capita.

Again though, at a primary beneficiary’s death, it is not just the division that counts. It is also the form of distribution. Will shares for a primary beneficiary’s descendants be distributed outright, or continue in subtrusts with at least one being created for each represented family unit in the next generation?

Even worse, what if there is a mismatch between these two outcomes? Should we strictly interpret the trust to respect the disparate outcomes, or should we chalk it up to a mistake?

Trust Language

In this case, Mr. Berman’s trust had different outcomes depending on whether or not a child survived him.

In the first division, at the time of Mr. Berman’s death, any shares created for grandchildren (which would only occur if a child predeceased him) would be held in subtrusts for the grandchildren and not distributed outright. Similarly, shares for children were to be held in subtrusts as well.

In the second division, at the time of a child’s death, the balance of the child’s share being distributed to Mr. Berman’s grandchildren (whose parent was the deceased child of Mr. Berman) were to be distributed outright to such grandchildren instead of being held in subtrusts.

In this case, however, one of Mr. Berman’s children survived him but later died before the revocable trust could be divided into separate shares or subtrusts. So, which outcome controlled?

The grandchildren argued that their shares should be distributed outright, because although their parent was deceased at the time of distribution, their parent’s condition of surviving Mr. Berman had been met. Although their parent’s one-third share had never been funded into the subtrust that would otherwise have been created had their parent been living at the time of distribution, the grandchildren argued that the division applicable at the death of their parent (and not Mr. Berman) under the terms of the parent’s subtrust should control.

The trustee (who was one of Mr. Berman’s surviving children), and Mr. Berman’s other surviving child, argued that the shares for grandchildren should be held in subtrusts, as called for at the death of Mr. Berman. Their reasoning was that allowing outright distributions due to the technicality of a child surviving Mr. Berman, but dying before division of the trust, would render the language regarding grandchildren’s trusts nugatory. So, they argued for the trust terms governing division at Mr. Berman’s death to control, instead of the terms applicable to the deceased child’s (never-funded) subtrust.

Appeal

The probate court refused to read each condition and term in a vacuum, and instead held that the trust should be read as a whole. And, in reading the trust as a whole, the probate court concluded that because the now-deceased child of Mr. Berman would not have received their share outright, the trust should not be read to allow the grandchildren to receive their share outright.

The grandchildren appealed, and the Court of Appeals reversed the probate court’s decision. Siding with the grandchildren, the Court noted their were two contingencies set forth in the trust. One would provide for grandchildren in trust if a child of Mr. Berman predeceased him. The other would allow outright distributions to grandchildren if a child survived Mr. Berman. The Court strictly followed the express language of the trust, and refused to hold that the two contingencies must be consistent.

In other words, the Court did not agree that part of the trust would be rendered meaningless or nugatory if the second contingency was ignored. As is the case in most states, it was assumed that Mr. Berman’s intent was clearly stated. There was no ambiguity or apparent scrivener’s error.

Key Lessons and Inside Baseball

The drafting and review lessons here are fairly obvious. If these two outcomes are mismatched, it helps to ask the settlor or testator (while living) if that is their intent. And, if not, it is easier to fix this during the life of the settlor or testator than it is to wait until the outcomes are disputed after their death. I would venture to guess that for the average advisor or strategist reviewing the trust, this mismatched outcome would have been missed or glossed over as unimportant.

But, we can also read between the lines here. The case noted that the significant asset of the trust was stock in a closely-held family corporation. The size of the corporation was presumably large enough that Mr. Berman’s stock generated estate tax. And, most importantly, it was one of Mr. Berman’s children who was acting as trustee and CEO of the corporation, and both of Mr. Berman’s children who were arguing for the creation of subtrusts for their nieces and nephews.

If you think about it, by not arguing for subtrusts, we would have a situation where (1) the stock for Mr. Berman’s surviving children was held in trust, but (2) the stock for Mr. Berman’s grandchildren (whose parent was deceased) would be held outright. It is not clear who the trustee of these subtrusts would have been, but assuming that one of Mr. Berman’s children acted as trustee of the subtrusts for grandchildren, it would have kept voting control in the second generation (subject to fiduciary duties). Instead, strict observance of the trust terms passed as much as one-third of the voting control on to the third generation and gave them a seat at the table for shareholder’s meetings.

We don’t know the family dynamics, but for things to get to this level, there may have been tension between the second generation and third generation. There may have been tension within the second generation, which got projected onto the third generation. There may even have been some frustration about distribution of the trust taking 7 years (and then being further delayed by this litigation). We don’t know, but this brings me to my primary lesson.

In this case, while it is easy to chalk this up to a drafting mistake by an attorney, it may not have been a drafting mistake. As I have noted before, even a perfectly-drafted estate plan can be derailed by family dynamics. A drafting attorney is not always privy to these family dynamics, because they may not be relevant while a matriarch or patriarch is living. It is only when the matriarch or patriarch is gone that we see a reduced need for civility.

Communication of the estate plan to the next generation can help avoid these outcomes. And, it may even be the case that this plan was indeed implemented with communication to, and/or initial buy-in from, the next generation. (Part of me doubts this because the case noted that Mr. Berman amended his plan several times, with the fourth restatement of his revocable trust controlling). But, regardless of outcome, there was an avoidable surprise here.

There are several AI and software solutions out there that will analyze a trust such as this and provide a summary. Some may even have identified the fork in the road in this trust that was later disputed. But, unless this fork in the road was specifically noticed and communicated by an actual person, this outcome might not have been prevented. There are a lot of family advisors out there doing good work on the governance side. But, good governance cannot ignore the technical side of things. We cannot yet farm out or abandon professional judgment, which is my purpose and “why” behind this newsletter - making sure the thirst for technical knowledge and analysis is not lost.