Table of Contents

Background

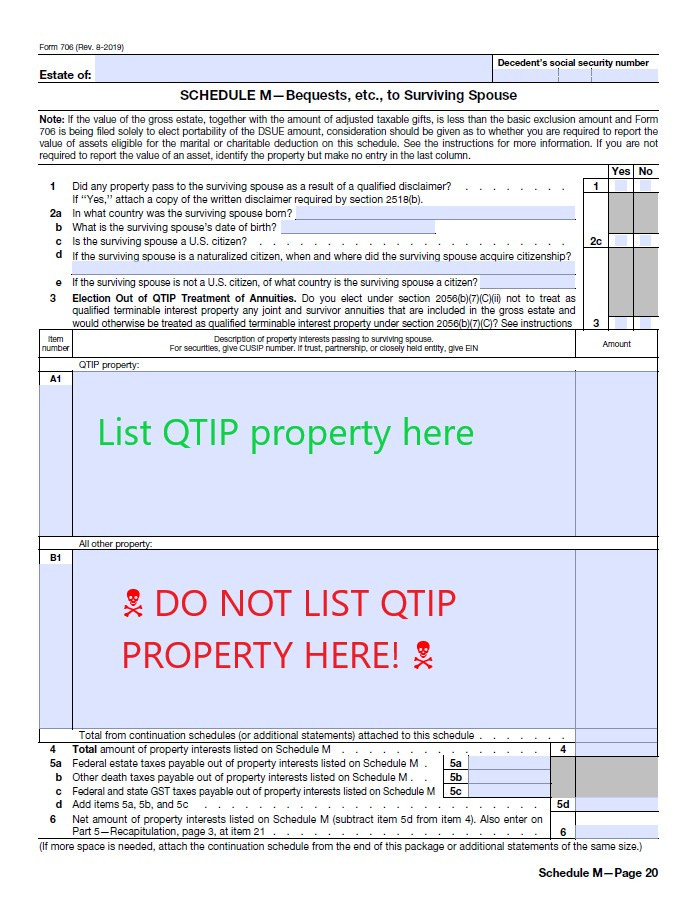

One of the most popular articles on this newsletter admonishes practitioners to be cautious about reporting on Schedule M of Form 706. Importantly, Schedule M distinguishes between QTIP property and non-QTIP property, in two separate parts. A frequent error on Schedule M is misreporting property for which a QTIP election is intended on the wrong part of the Schedule (i.e., the part on which non-QTIP property is included, namely direct transfers to a spouse). This image helps us contextualize this outcome (and yes, I realize the term “QTIP property” is redundant):

Some may have found the skull and crossbones to be needlessly bombastic – at least until a recent Tax Court Memorandum Opinion in Estate of Griffin v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo 2025-47. This case will be further discussed below.

For the time being, however, there is perhaps a simpler-yet-important distinction to be gleaned here beyond the QTIP election, which is included in a sidebar below. Skip ahead if you would like to review the case itself.

Technical Sidebar

A frequent debate among many practitioners is whether a transfer of title of assets to a trust should refer to a trust itself (by name and date of creation), or must instead designate the trustee as the appropriate transferee (again with reference to the name and date of the trust itself).

While this is largely state-specific, many states have shifted to (at least for real property) the view that a trust itself can be viewed as a legal entity, apart from the relationship between the trustee (as a figurehead role) and beneficiaries.

However, this case involves an interesting outcome for those who encourage the more-traditional designation of the trustee as transferee. Ironically, identifying the trustee as the transferee in this case was deemed to not be an addition (or amendment) to the trust itself, but instead as one factor in determining that the transfer was to a separate fund managed by the trustee for purposes of the estate tax marital deduction. While this factor was not the determining factor, it played a significant role in the outcome.

This case illustrates a key difference between a transfer to a trust itself, versus a transfer to a trustee of a trust – and how specific directions regarding the transfer to a trustee of a specific trust can be interpreted to create a new trust.

For background, transfers to a spouse who is a U.S. citizen at the time of the transfer are eligible for a gift or estate tax marital deduction. However, this deduction is not available for transfers of terminable interests – at least not unless the terminable interest itself is structured to be a deductible terminable interest. Without getting into the confusing definition, a terminable interest is a property transfer in which the spouse’s interest will terminate by death or lapse of time. Many trusts fall into the description of a terminable interest. However, IRC Sections 2056(b)(7) and 2523(f)(2) allow for a marital deduction to be claimed for qualified terminable interest property, colloquially abbreviated as “QTIP” and sometimes (albeit redundantly) referred to as QTIP property. But, as we will see below, it is certainly possible for a trust to not be considered a “terminable interest” to begin with.

For a marital deduction to be claimed for such property, satisfaction of the structural requirements under these Code Sections is our ticket to entry. Merely holding the ticket to entry, however, is not enough – you must actually enter into the QTIP regime by making an election on the Form 706 (for transfers at death) or Form 709 (for transfers during life).

It is this QTIP election, or lack thereof, that was addressed in Griffin – as well as the question of whether the election is even required to begin with under the terminable interest rule.

Case Facts

Martin W. Griffin had, during his life, established both a revocable trust and an irrevocable trust (the latter being identified as the “MCC Trust” in the case opinion). In an amendment to his revocable trust, two separate bequests – one of $2,000,000, and another of $300,000, were earmarked to be poured over to the (irrevocable) MCC Trust for the benefit of his spouse, Maria C. Creel, subject to certain conditions. The pourover language provided:

a. The Trust shall distribute the sum of Two Million Dollars ($2,000,000.00) to the Trustee then serving as the Trustee of the [MCC Trust] (as the trust may be amended), to be held for the benefit of Maria C. Creel. From this bequest, the Trustee of the [MCC Trust] shall pay to Maria C. Creel a monthly distribution, as determined by Maria and Trustee to be a reasonable amount, not to exceed $9,000.00 (such $9,000.00 to be adjusted, from the initial funding date, by a factor for the Consumer Price Index, as reasonably determined by the Trustee, in his sole discretion).

b. In addition to sub-part (a) above, the Trustee shall distribute the sum of $300,000.00 to the Trustee then serving as the Trustee of the [MCC Trust] (as the Trust may be amended), to be held as a living expense reserve for Maria [C.] Creel, to be distributed to her in the amount of $60,000.00 per year ($5,000.00 monthly) (plus earnings on such amount as determined by Trustee), for up to 60 months from the time of the initial funding of this Bequest. Any undistributed amounts of this Bequest upon Maria C. Creel's death shall be paid to her estate.

After his death, the executor for Mr. Griffin’s estate reported both bequests on the Part B of Schedule M – the section with the skull and crossbones in the image above – with the intent of claiming the QTIP election (as opposed to listing it as QTIP property in Part A). In a Notice of Deficiency for the estate tax, the Service claimed that the subject property was included in the (taxable) estate while also imposing an accuracy-related penalty.

Tax Court Holding

Both the estate and Service filed motions for partial summary judgment, on the issue of whether the “two bequests are includable in Martin W. Griffin’s estate.” (As an aside, this does not appear to be a complete statement of the issue at first glance, as even QTIP property is included in the “gross” estate – I believe what the Tax Court and parties appropriately meant here was “taxable” estate which is the gross estate, net of deductions like the marital deduction. I bring this up because when many practitioners speak to the question of whether or not property is included in the “estate,” they often intend to refer to the gross estate. However, in the context of determining whether property is a terminable interest or a deductible terminable interest, it is appropriate to examine it through the lens of inclusion in the taxable estate as the Tax Court did here.)

With respect to the $2,000,000 bequest, the Tax Court did not analyze whether the structure of the bequest (i.e., the pourover) qualified for the QTIP election. Instead, it analyzed whether the QTIP election had validly been made on Form 706, Schedule M and concluded that it had not – thus deeming it unnecessary to address the issue of whether the other QTIP requirements were satisfied.

It is important to note, however, that the Tax Court believed the estate admitted that no effective QTIP election was made due to the reporting error. The estate subsequently tried to play an administrative “gotcha” by claiming that the Service failed to bring up the failure of the QTIP election during the audit process, but the Tax Court concluded (as paraphrased from the body of the opinion and footnote 3 thereof) that the claim of an estate tax deficiency technically could be implied from the failure of the QTIP election itself, thus leading to a loss of the marital deduction, thus leading to inclusion of the subject property in the (taxable) estate, all of which did not need to be explained in a step-by-step fashion. In other words, as noted by the Tax Court in footnote 3, “[the Service] did not need to do the estate’s job for it.”

This reporting error, however, was not at issue for the $300,000 bequest because the estate successfully argued that this was not a terminable interest to begin with. Note that the QTIP election need only be made for interests that would otherwise be terminable interests but for the satisfaction of IRC Sections 2056(b)(7) and 2523(f)(2). In order to arrive there, the Tax Court examined whether Mr. Griffin had intended to create a new $300,000 trust as a separate “fund” of the existing MCC Trust by the pourover instruction, or instead had intended to add the $300,000 to the existing corpus of the MCC Trust (the irrevocable terms of which arguably created a terminable interest and could not be amended by a pourover).

The Service argued that this should be an addition to the existing trust, in part because the directions for pourover bequest referenced the trustee of the MCC Trust by position instead of by name. However, the Tax Court did not agree. Instead, it determined that this was a separate trust set up to be administered by the trustee of the MCC trust.

On that note, the Tax Court seemingly focused on one core issue when determining whether this separate trust was a terminable interest – the issue of inclusion in the surviving spouse’s (Maria Creel’s) estate. (As another aside, this brings up a third term of art when examining a blanket reference to inclusion in the “estate” – the possibility that property will pass to the probate estate of a decedent.) The bequest provided for the principal (plus earnings) to be distributed monthly for 60 months, with the balance being paid to Maria Creel’s estate if she were to die before all distributions were made. Hence, the Tax Court concluded that this is not a terminable interest and thus qualifies for the marital deduction.

Key Takeaways

This case illustrated a clever workaround for misreporting of QTIP property. By successfully arguing that the $300,000 bequest was not actually a terminable interest, the reporting error was nullified as technically all property passing to a spouse that is not a terminable interest would be appropriately reported on Part B (the non-QTIP portion) of Schedule M.

Note, however, that the QTIP election is not the only way to obtain a marital deduction for a terminable interest itself. Many marital trusts are set up to give the surviving spouse a general power of appointment, which is enough to create a deductible terminable interest when accompanied by the other traditional requirements. Such an interest may be appropriately reported as non-QTIP property, but it also raises the question of whether the general power of appointment itself disqualifies the trust from the QTIP election. I have claimed so before, but other thought leaders have pushed back against me on that point as the Code technically does not forbid such an outcome. It may be the case that only a presently-exercisable general power of appointment might disqualify a trust from a QTIP election and force a full marital deduction. Clarifying the type of trust in play is extremely important, as illustrated above.

For 706 and 709 preparers, however, this continues to be an important issue when it comes to the possible misreporting of QTIP property. Relief through a PLR may be the only possible fix depending on when the error is caught, assuming the taxpayer qualifies. For now, however, it is important to note that the estate did not put forth a compelling argument of substantial compliance in this case - so it may not be outside of the realm of possibility that such an argument could later succeed in the absence of a PLR. All the estate claimed is that the Service did not serve up to them (pun intended) the faultiness of the QTIP election on a silver platter as part of the audit or assessment process. Obviously doing it right the first time is important, but I also caution against a narrow procedural reading of the opinion.

However, I also think it is important to highlight that there are several trickle-down effects here. Many returns are filed for the sole purpose of making a portability election, and the amount of a deceased spouse’s unused exclusion is increased dollar-for-dollar by the QTIP election in most cases. In such a case, the Service has the authority (under Treas. Reg. 20.2010-3(d)) to examine the portability return at the death of the surviving spouse for purposes of determining the DSUE that is available to the surviving spouse for purposes of determining the applicable credit against estate tax. Such an examination could, for example, reduce DSUE due to a faulty QTIP election on the portability return.

A failed QTIP election may also mean loss of a prior deceased spouse’s GST tax exemption, as technically the reverse QTIP election to allocate GST exemption is reliant on a valid QTIP election. I would also go so far as to argue that a reverse QTIP election might be unavailable or faulty in a portability return filed late under Rev. Proc. 2022-32, as unused GST exemption gets automatically allocated at the original due date (with timely extensions) for the Form 706.