Revocable Versus Irrevocable Trusts: A High-Level Framework

Examining how revocability of transfers drives the type of trust

This article is part of the series on everything you’ve ever wanted to know about trusts.

For a series index and the first article in this series, click here.

For the prior article in this series, click here.

To skip to the intro, click here.

Table of Contents

Intro

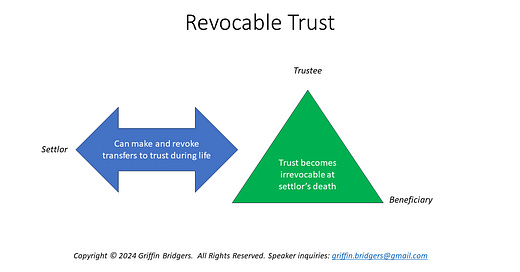

In prior articles, we discussed the parties to trusts and how we break down types of trusts by time of funding (i.e., during a settlor’s life versus at a settlor’s death). As alluded to in my last article, one “hybrid” type of trust when it comes to time of funding is the revocable trust, as the subtrusts created at a settlor’s death often function the same as testamentary trusts that might get created under a will (but with some advantages over traditional testamentary trusts to be later discussed).

Today’s article is all about distinguishing between revocable trusts versus irrevocable trusts. But, we will do so from the frame of who can take property out of the trust.

Putting Property In

As discussed in the first article in this series, it is possible for a person to fulfill multiple roles in a trust – settlor, trustee, and beneficiary. Proper structuring of trusts relies on predictability of who fills each role. In this vein, we should determine the primary “hat” (settlor, trustee, or beneficiary) a person happens to be wearing at the time of any particular property transfer in or out of a trust.

While perhaps oversimplified, only a person wearing the settlor “hat” can put property into a trust.

But, what if a trustee or beneficiary puts their own property into a trust, whether it is an actual transfer or the simple release or lapse of a right to take out property (discussed below)? This is permitted, but it is not optimal because it may cause that trustee or beneficiary to become a settlor with respect to their contributions to the trust. Ironically, many trusts don’t account for this possibility. Even if a revocable trust is involved, a trustee or beneficiary who accidentally becomes a settlor may lack the formal powers to take back their property because they do not sit in the seat of being a named settlor in the trust. For this reason, I will refer to settlors who actually sign the trust as named settlors.

There is also a hierarchy of powers to add or withdraw property in terms of how the trust or person is treated from a tax law and property law perspective:

Named settlor > Beneficiary’s power of withdrawal > Any person’s nonfiduciary power of appointment > Trustee’s powers of distribution > accidental settlor

In this formula and hierarchy, what we will later find out is that we must determine the primary hat worn by a person who fills multiple roles. But, regardless of primary hat, it may be the case that hats cannot be distinguished. So, for example, a beneficiary who is also trustee may have the trustee’s fiduciary duties bleed over into nonfiduciary powers held by a beneficiary.

Revocable Trusts

Often, the distinction between a revocable and an irrevocable trust revolves around a named settlor’s retained right to revoke the trust. But, from a practical perspective, I often see this as an incomplete conclusion. Why? Because if a trust is revoked, it is really a revocation of a named settlor’s transfers to the trust. In other words, under Griffin’s rules, a revocable trust has two hallmarks:

(1) A named settlor can revoke their transfers to the trust or trustee; and

(2) In so doing, the named settlor does not have to provide any consideration or exchange value back to the trust or trustee.

Of course, revocation of the trust instrument itself can result in distribution of the property back to the settlor, but perhaps in a different capacity (such as beneficiary, or holder of a power of withdrawal). This wouldn’t necessarily be a true revocation of transfers, because it adds a step and possibly invokes a trustee’s consent. But, when we consider revocation with respect to a trust instrument itself or specific terms of a trust instrument, we find that what we will come to know as an irrevocable trust no longer fits that strict framework. Many states have adopted some form of the Uniform Trust Code (UTC), which allows terms of an irrevocable trust to be modified in certain situations. Some states also recognize a de facto “revocation” of an otherwise irrevocable trust by a trustee through a process called decanting, which is an extension of a trustee’s distribution power.

Irrevocable Trusts

Semantics and academic arguments aside, when we explore an irrevocable trust from the perspective of property being transferred in and out, we find the following hallmarks:

(1) A settlor cannot take property out of an irrevocable trust without at least putting back in or promising to put back in property of equivalent value (a sale, exchange, or loan), which usually requires trustee consent;

(2) If the settlor puts in more than they get back from the irrevocable trust, this invokes gift tax rules and fraudulent/voidable transfer rules; and

(3) If the settlor puts in less than they get back from the irrevocable trust, this invokes gift and estate tax rules.

Long story short, with a revocable trust, a settlor can revoke transfers to the trust while wearing the “settlor” hat. In an irrevocable trust, a settlor cannot revoke transfers to the trust while wearing the “settlor” hat. If a settlor reserves for themselves the right to take some property out of a trust, this is more akin to a right of withdrawal which we will later discuss. And, for irrevocable trusts, a settlor’s right to remove property may be subject to fiduciary duties, voidable transfer rules, or veto by a trustee.

But, all three parties to a trust – settlor, trustee, and beneficiary – might respectively have the power(s) to send property out of the trust. The treatment of the trust might depend on what hat a person is wearing when property is removed from a trust.

Fraudulent and Voidable Transfers

When we look at the transfer of property into a trust, whether by a named settlor or accidental settlor, creditor protection issues come into play. For a settlor who has an unrestricted right to revoke transfers to a trust, a creditor of the settlor can usually force a settlor to exercise this right. Even after a settlor’s death, many states allow revocable trust assets to be used to satisfy claims against the settlor’s estate even though a revocable trust becomes irrevocable (with respect to transfers by a settlor) at a settlor’s death.

But, where a settlor’s transfers to a trust are irrevocable, fraudulent or voidable transfer statutes might come into play. This allows a creditor of a settlor to void or undo certain transfers to trusts (which are not equal sales or exchanges) if the transfer renders a settlor insolvent, or if the creditor can prove that the settlor had the intent to defraud the creditor at the time of the transfer. In some states there may be a limited lookback period (2-5 years) for application of these types of statutes, but in other states there may not be a defined lookback period.

Later we will discuss how creditor protection issues apply to beneficiaries and trustees, but estate planning trusts should include a spendthrift clause which prevents most creditors (depending on the state) from forcing a distribution to satisfy claims against a beneficiary. Where distribution rights are mandatory, however, or where a beneficiary has a power to withdraw trust assets, these may create an angle for a creditor to use trust assets to satisfy claims against a beneficiary.

Powers of Withdrawal and Appointment

We will cover these in a later article in this series, because powers of appointment cover a lot of ground. Generally, a power of appointment is a power to take property out of a trust. But, where this gets tricky is that a person holding a power of appointment does not necessarily have to wear the hat of settlor, beneficiary, or trustee. In fact, powers of appointment create their own parallel, alternative structure – akin to Marty and Doc’s journey back to a parallel year 1982 in Back to the Future II. There are three other hats – donor, holder, and appointees/donees – that create an almost-convenient parallel correlation to the hats of settlor, trustee, and beneficiary under a trust.

For certain property law and tax law purposes, we will later find out that a trustee’s distribution powers are indeed treated like a power of appointment. The big question is whether the powers have fiduciary duties attached. Where there are fiduciary duties, we may cross the “hats” a person wears between the two parallel roles. A donor of a power of appointment is usually always a settlor. A holder of a power of appointment could acquire the hat of trustee, even if there is no intent for fiduciary duties to attach to their power of appointment. And, appointees/donees could acquire the hat of beneficiary for certain purposes regardless of the presence or absence of fiduciary duties.

Distribution Powers

Later, we will discuss the various forms of trustee distribution powers. These powers allow property to be removed from a trust, but as alluded to above a trustee’s powers are subject to fiduciary duties.

Summary and Conclusion

To recap, here is a framework through which to view trusts by powers to add or remove property:

Named settlors have the right make and revoke transfers to a revocable trust without a trustee’s consent and without intervening fiduciary duties;

Named settlors have the right to make transfers to an irrevocable trust, but property put into the trust cannot be reacquired unless the named settlor at least puts back in (or makes a legally enforceable promise to put back in) property of equal or greater value;

For named settlors to enter into an exchange, sale, or loan with a trust, trustee’s consent is required and this may invoke the trustee’s fiduciary duties;

Transfers or net transfers to a trust by a settlor, whether named or accidental, may be subject to fraudulent or voidable transfer laws and thus not fully protected from creditors’ claims;

A beneficiary or trustee could become an accidental settlor by adding property to a trust, whether directly or by release or lapse of certain powers, and by not being named settlors these transfers may be irrevocable;

Beneficiaries, or even persons who are not beneficiaries of a trust, may have a power of appointment to remove property from a trust with no fiduciary duty attaching, except in some scenarios (to be later discussed) where a beneficiary also wears the hat of trustee; and

Trustee’s distribution powers are defined by the trust and state law, and are usually subject to fiduciary duties.

In the next article, we will explore a trustee’s distribution powers in greater detail.