C and S Corporations for Estate Planners: Constructive Dividends and Intro to Stock Redemptions

Introducing adverse estate planning distribution outcomes for C corporations

This is the fourth installment of C and S corporations for estate planners.

For the prior article in this series, click here.

For the first article in this series and a series index, click here.

Table of Contents:

Intro

In the last article, we discussed how previously-taxed earnings are tracked from an accounting perspective. For a C corporation, earnings and profits (E&P) forms the basis for tracking accounting income, whether taxed or tax-exempt, to determine what might be taxed a second time to shareholders upon distribution. For an S corporation, previously-taxed income and tax-exempt income is tracked in shareholder basis since shareholders are taxed on this income; however, S corporations with prior C corporation operating history keep tracking E&P with a new, superseding layer called an accumulated adjustments account (AAA).

Both E&P and AAA form the basis for determining what might be treated as a dividend, whether or not taxable. And, as we will see, it can be difficult to circumvent these rules – creating bad outcomes for C corporations, but possibly creating good outcomes for S corporations (the subject of the next article).

Scope of Dividends

As we discussed last time, distributions from C corporations that are attributable to share ownership are typically treated as dividends and thus subject to income tax under IRC Sections 301 and 316.

For a C corporation, dividends are usually taxed as ordinary income; however, qualified dividends may be taxed as net capital gain (and thus entitled to the 0%, 15%, or 20% rates applicable to net long-term capital gains). While the exact definition of qualified dividend income under IRC Section 1(h)(11) is a bit outside of the scope of this discussion, the bare minimum requirement is usually an intentionally-declared dividend (which usually applies to all shareholders, in total or by class of shares). In addition, the shares to which the dividend is attributable usually must have been held for at least 60 days during the 121-day period beginning 60 days before the ex-dividend date.

In this vein, what might be an unintentional dividend? Perhaps it is a loan from a corporation to a shareholder. Perhaps it is an overpayment of compensation to a shareholder who also purports to act as an employee or contractor. Perhaps it is an interest payment on a loan from a shareholder to the corporation. In all of these cases, you have what is sometimes called a constructive dividend. Since constructive dividends are not usually declared for all shareholders, they are usually taxed as ordinary income.

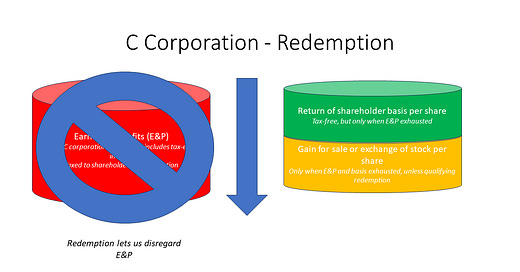

Another unintentional dividend can arise where a C corporation buys back the shares of a shareholder – usually called a redemption. Typically, a sale of stock should be treated as a sale or exchange which results in (1) a tax-free return of basis, and (2) taxable gain if the amount realized is greater than the basis. But, IRC Sections 302 and 303 contain somewhat-complicated rules regarding the sale or exchange treatment of redemptions.

What is at stake is a recasting of a stock redemption into a dividend. This has two effects. The most obvious effect is that any gain which would otherwise be recognized is taxed as ordinary income. But, the more nefarious effect is that the return of basis, including basis that is stepped-up at the death of a shareholder, could also be taxed as ordinary income instead of being received tax-free (when coming from a C corporation). Keep in mind that this dividend treatment only applies to the extent of E&P, however.

A better way to think of this is a priority of later cakes. If you have a redemption, the layer of E&P disappears – meaning you can then move to a mixed layer of return of basis and built-in gain (which is a bit different from an S corporation as we will see in the next article, as we go on a share-by-share basis for a C corporation versus aggregating all shares for an S corporation). But, if you receive property from a corporation that becomes cast as a dividend, then the entire layer of E&P must be exhausted before you can consider any other tax treatment.

I have oversimplified the analysis in this repeat image below, since it is rare (if ever) that basis can be isolated in favor of built-in gain in shares. But, in estate planning, we could have stepped-up basis stock that lacks the third layer in the event of the death of a shareholder. This is a theme we will cover in the next few articles.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to State of Estates to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.