QTIP Trusts and Rights of Recovery: IRC Section 2207A

A hidden, but important, issue for those drafting and administering QTIP trusts

This is a continuation of the series on everything you ever wanted to know about estate planning trusts, under the subtopic of marital trusts. For an intro and index to this series, please click here. The linked article will have a series index that gets updated periodically as well, so please bookmark it.

Table of Contents

Intro and Background

This will be a brief introductory discussion, which is by no means intended to be comprehensive – especially because it would mean backtracking to cover tax apportionment comprehensively as well.

But, for the time being, it helps to consider that tax apportionment at the top of the bell curve is based on the fact that the estate tax is tax-inclusive – meaning that property transfers at death are reduced for the proportionate share of estate tax attributable to each. (This is contrasted with the gift tax, which is tax-exclusive – meaning that the transferor pays the gift tax in addition to the actual gift.) In some cases, property transfers do not generate estate or gift tax – namely transfers that qualify for the marital deduction or charitable deduction. And, as we will later find out, payment of estate taxes from marital or charitable gifts reduces the actual marital deduction or charitable deduction itself. This can, in the worst case, lead to a circular calculation which sends us into oblivion.

Note, however, that the marital deduction defers estate tax as previously discussed. So, at a surviving spouse’s death, their gross estate will include not just their own assets, but also assets forced into the survivor’s gross estate by virtue of the prior marital deduction. However, if there is a QTIP trust, our traditional tax apportionment principles go out the window.

As previously discussed, QTIP-elected assets are included in the survivor’s gross estate under IRC Section 2044. Further, in the event of a gift of QTIP-elected assets, the deemed “release” of an income right by the surviving spouse through that gift is treated under IRC Section 2519 as a gift of the underlying trust principal (i.e., a gift of the 100% remainder interest and not the present value of the income interest).

Where a QTIP-elected trust is involved, can we count on traditional tax apportionment? Further, does the tax-exclusive nature of gift tax on gifts of QTIP-elected property mean that the survivor must pony up to pay gift tax out of their own personal assets?

Answers to both questions can be found in IRC Section 2207A.

Intro to 2207A

IRC Section 2207A gives the surviving spouse the power to elect to pay any incremental increase in estate or gift tax under IRC Sections 2044 or 2519, respectively, from the QTIP-elected assets themselves. In the case of estate tax, this changes apportionment because the survivor’s own assets will then only be reduced for the estate tax (if any) on the survivor’s own non-QTIP assets. And, in the case of gift tax, this changes the gift tax from being tax-exclusive to tax-inclusive where lifetime gifts of QTIP-elected assets are made.

This election is an election that is personal to the surviving spouse during life, or to their executor following the survivor’s death. However, in this vein, the executor is bound by the survivor’s directions regarding the recovery election made during life – whether through a will or revocable trust. In other words, if the survivor includes a provision in their will directing the executor not to make the election, then the executor cannot make the election. Likewise, the survivor can grant the executor the discretion to waive the right of recovery. As we will later discuss, the presence or absence of these instructions has special gift tax significance.

Ultimately, this is treated as a right of recovery from the person receiving the property. This means a failure to recover before the termination of a QTIP trust does not preclude subsequent recovery from remainder beneficiaries – the IRS recently tried to argue otherwise and lost. Likewise, a failure to make or waive the election for gifted property may not preclude subsequent recovery of gift tax from donees of property that was subject to the special gift tax rule of IRC Section 2519.

Examples

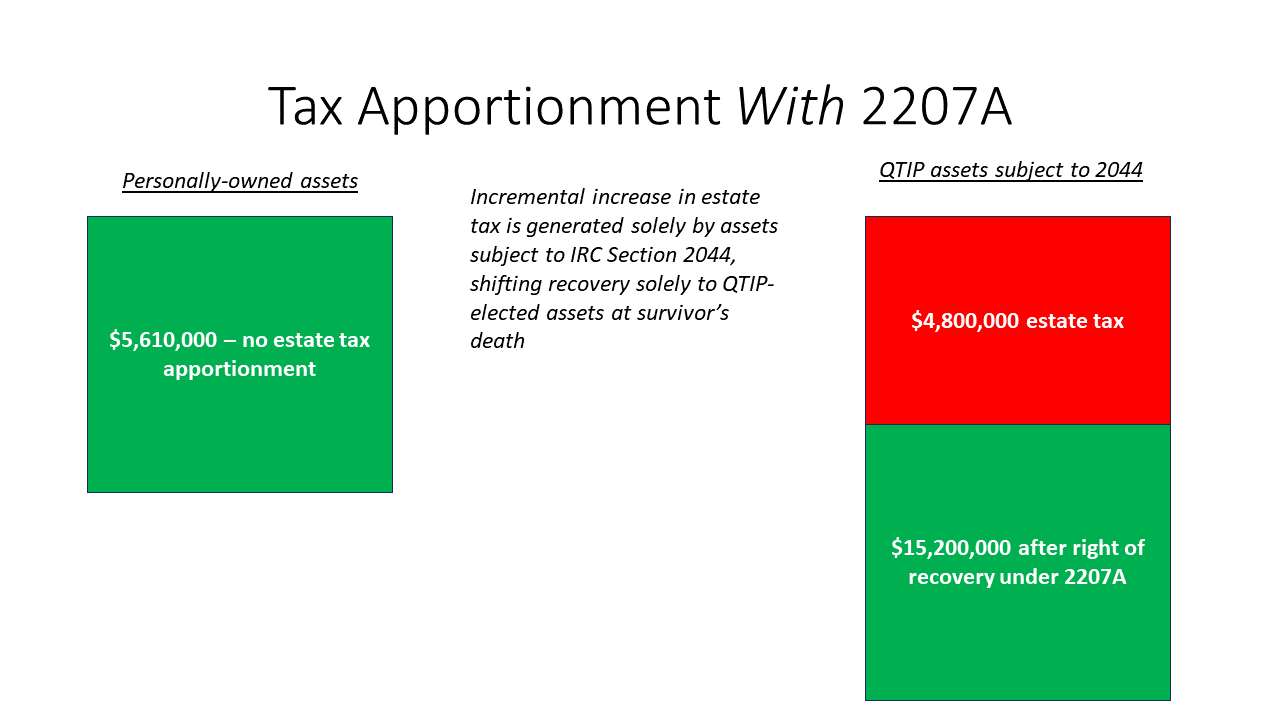

Let’s say a survivor has personally-owned assets worth $5.61 million, and is the beneficiary of a QTIP-elected trust worth $20 million. In such a case, the gross estate is $25.61 million. With the current (2024) estate tax basic exclusion of $13.61 million, this means there will be an estate tax of 40% on $12 million, or $4.8 million, by operation of the applicable credit. (For the sake of simplicity, we will assume there are no deductions against the gross estate or lifetime taxable gifts, and we will also assume that the deceased spouse’s estate did not make a portability election to leave DSUE for the survivor).

Under traditional apportionment, this $4.8 million in estate tax would be taken proportionately from both the survivor’s personally-owned assets and the QTIP-elected assets. The outcome is as follows:

However, the election under 2207A provides that the incremental increase in estate tax from the inclusion of QTIP-elected property in the survivor’s gross estate under IRC Section 2044 would instead be recovered from the QTIP-elected assets themselves, or the remainder recipients thereof. In such a case, prior to application of 2044, the $5.61 million gross estate is less than the $13.61 million exclusion – meaning that there is zero estate tax before application of 2044. This means all estate taxes are attributable to the increase caused by inclusion of QTIP-elected assets in the gross estate under IRC Section 2044. The outcome is that the estate tax is exclusively taken from the QTIP-elected assets instead of the survivor’s personally-owned assets.

In effect, this creates an ordering rule where we must first take into account the incremental recovered estate tax under IRC Section 2207A. If the QTIP-elected assets do not generate all estate tax, then the balance is subject to traditional apportionment from non-QTIP assets (to the extent not subject to estate tax marital or charitable deductions) - whether directed under state law, or altered under the will or revocable trust.

Effect on Post-Sunset Planning

The weight of estate tax planning for married couples has shifted from the traditional A/B formula, to an approach which allows for portability of a deceased spouse’s unused exclusion (DSUE). The outcome is a shift to preferential funding of a QTIP-eligible trust, as each dollar of value transferred to the QTIP trust (or directly to the surviving spouse) creates a corresponding dollar increase in the DSUE being preserved.

This often expands the universe of tax planning options available to the surviving spouse – especially because the DSUE is (1) not subject to the sunset and (2) creates an addition coupon for a basis step-up at the survivor’s death.

Within this type of planning, however, we must consider the trickle-down effects of deferred estate tax on the QTIP-elected assets with respect to the right of recovery under IRC Section 2207A. Clear instructions as to the surviving spouse’s intent to make or waive the election, especially with respect to the executor’s discretion or lack thereof, are increasingly important. Without clear instructions, an executor’s choice to make the election can have an adverse gift tax consequence as will be discussed in the next section of this article.

First, however, please note that this right of recovery also applies to lifetime gifts of QTIP-elected assets by the survivor. For any lifetime gift by a surviving spouse, Treas. Reg. 25.2505-2(b) provides that DSUE will be used before basic exclusion in determining applicable credit against gift tax. The outcome is a lower possibility that the right of recovery would indeed apply to a QTIP trust so long as any DSUE exists. This makes it difficult to leverage the right of recovery against QTIP-elected assets for lifetime gifts if that is the intent, since there would be no gift tax until both DSUE and basic exclusion are used up. But, post-sunset, a lower basic exclusion amount could increase the possibility of sourcing gift tax from QTIP-elected assets if these are indeed the assets being gifted.

Likewise, the existence of DSUE at the death of a surviving spouse reduces the possibility of recovery from the QTIP-elected assets. In this vein, however, lifetime gifts of personally-owned illiquid assets can have the indirect effect of shifting recovery for estate tax on both lifetime adjusted taxable gifts, and the taxable estate, to (perhaps liquid) QTIP-elected assets at the survivor’s death.

Unexpected Gift Tax Outcomes

What often flies under the radar is the effect of Treas. Reg. 20.2207A-1(a)(2) on both the survivor’s estate, and the remainder recipients of QTIP-elected property. While the effects of a waiver of the election on the survivor’s estate are readily apparent – a shift to traditional tax apportionment as illustrated above – this Regulation creates a deemed gift if the executor themselves makes the election independent of written guidance from the survivor.

In such a case, the deemed “gift” is from (1) the persons benefitting from the property (i.e., the remainder recipients of the QTIP-elected property) to (2) the persons from whom the recovery could have been obtained. Now, it is important to note that sometimes (but not always) the gift may be between the same recipients – leading to the possibility of low or no gift tax. This deemed gift, however, occurs when the right of recovery can no longer be exercised under applicable law (usually state law dealing with apportionment), and if delayed is treated as a below-market loan bearing interest.

Instead of explaining this rabbit hole further, please note that Treas. Reg. 20.2207A-1(a)(3) turns off this deemed gift treatment if (1) the surviving spouse actually waives the right of recovery under their will or revocable trust, or (2) the surviving spouse gives the executor the discretion to waive the right of recovery under their will or revocable trust. In such a case, since the persons who would benefit from the recovery cannot compel the executor to exercise the right of recovery, there is no deemed gift.

Conclusion

While there is a lot more that can be said on both this subject (the right of recovery), and tax apportionment in general, the downstream effects of the right of recovery on the deferral-driven nature of the QTIP election should be considered. While a married couple may have no present estate tax risk, future asset appreciation and/or reductions to the basic exclusion amount can have outsized effects on projected estate taxes at the survivor’s death. Considering the right of recovery, and strategies relating thereto, will become increasingly important depending on what happens to the estate and gift taxes in the future. It can also have an effect on tax elections to be made by an executor, or surviving spouse, at the death of the first spouse to die.