This is a continuation of the series on everything you ever wanted to know about estate planning trusts. For an intro and index to this series, please click here. The linked article will have a series index that gets updated periodically as well, so please bookmark it.

Note also that this article is provided for general educational purposes. It does not substitute for legal or tax advice, and is not a complete primer on all risks and requirements for a GRAT. Numbers and calculations provided in this article are for illustration purposes only, and complete accuracy is not guaranteed.

Table of Contents

General Purposes

There are three common goals in estate tax planning through lifetime transfers – often colloquially known as (1) freeze, (2) squeeze, and (3) burn.

With freezing, you can never truly remove the value of a non-consumable asset from your estate tax base. It is included in your estate tax calculation either at the value at the time of gift, or the value at the time of death. Assuming assets appreciate in value over time, the incentive to make a lifetime gift is removing future growth from your estate tax base – hence “freezing” the value for estate tax purposes.

Squeezing examines the fact that gifted fractions of property may have a value that is less than the whole. These valuation discounts often come in two flavors. One is a discount for lack of marketability, sometimes with a companion discount for lack of control, on a gift of an asset such as a closely-held business interest. Another is a time-value of money discount when we gift away a split-interest, while retaining a qualified retained interest for ourselves – often in the form of an income or use right for a term of years, and sometimes in the form of a remainder (reversionary) interest at the end of a term of years.

Finally, the “burn” alludes to a combination of (1) expected consumption spending to deplete our estate tax base, and (2) strategic payments of taxes at lower effective rates than estate tax rate in order to further deplete our estate using arbitrage. The latter often involves the use of grantor trusts, under which the creator (or sometimes a beneficiary) of the trust is treated as the income tax “owner” of trust assets. This allows for the deemed owner to pay income tax on behalf of trust beneficiaries, without necessarily making a gift to them.

The grantor-retained annuity trust, or GRAT, can be an effective way to accomplish all three of these goals, by leveraging time-value of money discounts with two gambles – one, that the grantor will outlive a trust term, and two, that the growth of the value of trust assets during the trust term will exceed a certain IRS rate.

Basic Structure

A GRAT in its most basic form involves two elements:

A retained income interest held by the grantor, structured as an annuity– often expressed as a set percent of the initial fair market value of assets transferred to the GRAT - payable for a set term of years; and

A remainder interest passing to other family members, often children, usually in a direct distribution or transfer to a GST-nonexempt trust.

The economics of the GRAT are dependent on the IRC Section 7520 rate for the month the GRAT is funded. This rate is usually expressed as 120% of the mid-term applicable federal rate, rounded to the nearest 0.2%. This rate helps us determine (1) the minimum annuity payment needed for the GRAT to be successful, and (2) the likelihood that the grantor will outlive the term of the GRAT.

On the latter point, the biggest kryptonite to the GRAT is IRC Section 2036. This Code Section applies to any transfers made by the grantor during life over which, at the time of death, the grantor has retained possession, enjoyment, or control – including an income interest in a GRAT. So, if the grantor hopes to achieve the “freeze” goal of the GRAT, they must outlive the trust term. If they do not, then in the worst case, estate tax will apply as if the grantor was still the owner of GRAT assets at the time of death – with the GRAT assets being taxed at their estate tax value at death (instead of their gift tax value during life). (Note that there is the possibility of less than the FMV of GRAT assets being included in the gross estate, if the annuity amount divided by the 7520 rate at the time of death is less than such FMV - which tends to favor longer-term GRATs with lower annuity amounts, combined with a high 7520 rate at the grantor’s death.)

For the former point above (minimum annuity payment), there are bounds dependent on the term of the GRAT that may frustrate its purposes. For example, if a $1,000,000 GRAT pays 25% to the grantor for a 10-year period, it is likely that the GRAT will be exhausted and the grantor will end up no better off. However, if that same 10-year, $1,000,000 GRAT pays only 2% per year, there won’t be much of a gift tax discount. The goldilocks zone of GRAT planning balances risk of depletion with benefits of a gift tax discount. Either way, the annuity payment should at least equal the 7520 rate for the month of funding the GRAT.

In this vein, however, a minimum term of 2 years is often recommended. There is no maximum term, but choice of a term that the grantor will outlive is usually recommended. Numerous Treasury proposals over the years have explored a minimum GRAT term (5-10 years), but none have been enacted. Further, for longer-term GRATs, proposed Treasury Regulations would (if published as a final rule) disregard pre-sunset use of estate tax basic exclusion amount for purposes of computing the post-sunset applicable credit against estate tax if (1) a GRAT is included in the grantor’s gross estate, and (2) the initial gift tax present value of the GRAT remainder was more than 5% of the value of assets transferred thereto.

Of course, there is also market risk. If the growth of the value of the GRAT does not exceed the 7520 rate over the term of the GRAT, then this leaves no remainder to be distributed. The outcome is that 100% of the GRAT gets distributed back to the grantor. Note, however, that this does not leave the grantor in any worse of a position than they would have been in had they just held on to the GRAT assets to begin with. And, because a GRAT is a grantor trust, tax losses from the GRAT in this loss scenario could be passed through to the grantor during the term of the GRAT.

Finally, on that note, the GRAT usually works best when funded with marketable securities, because they are easy to value. While other assets can be used, there is a risk to funding a GRAT with hard-to-value assets. If the income of the GRAT (generated by such hard-to-value assets) is not sufficient to pay the annuity amount for any given year, then some of the actual principal of the GRAT must be distributed in-kind – creating the need for a valuation (which can be difficult and expensive and, which if not accurate, can cause the whole GRAT to fail). Such an in-kind distribution is much easier to accomplish with easy-to-value securities. For this reason, GRATs are often (at least initially) funded with a single position in securities. And, since a GRAT is a grantor trust, there usually is no recognition of gain on the distribution of securities in-kind to satisfy a pecuniary annuity amount under IRC Section 663(a)(1).

All that being considered, however, the GRAT can create significant gift tax valuation discounts. Before illustrating how, there are a couple of points you should note. One, the higher the 7520 rate at the time of the gift, the lower the gift tax discount on the present value of the remainder being gifted away. Two, the annuity amount can increase year-to-year, but by no more than 120 percent each year.

Example Calculation for NVIDIA Stock to GRAT

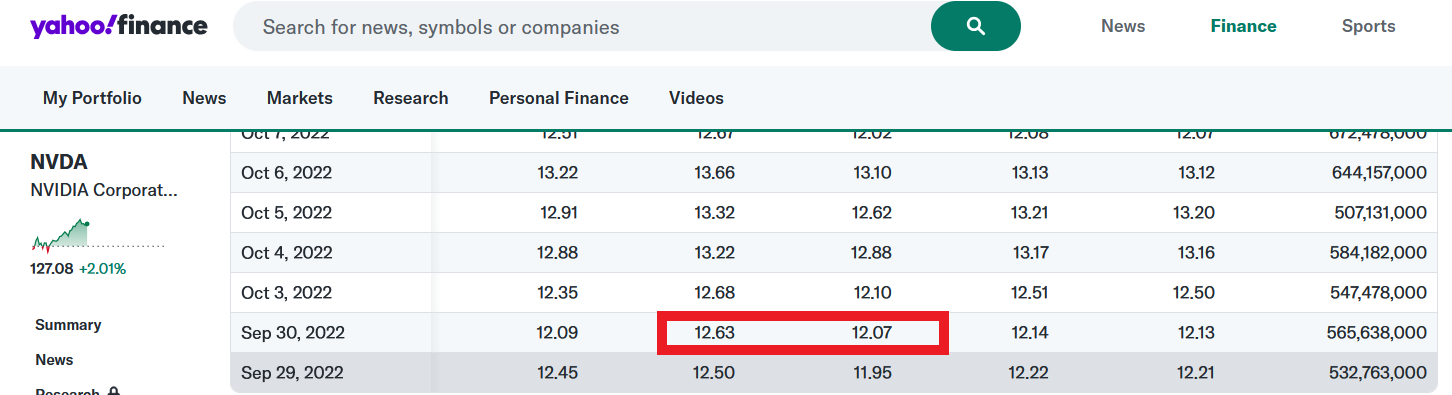

Let’s take an example of a client who, on September 30, 2022, held 100,000 shares of NVIDIA stock. On that date, NVIDIA closed at $12.14 per share. For gift tax purposes, we do not use the closing price but instead the average of the high and low trading prices on that date - $12.63 and $12.07 – for a mean of $12.35 per share (see Treas. Reg. 20.2031-2).

Source: Yahoo.com

So, the client entered into a two-year GRAT, with an initial value of $1,235,000. The 7520 rate for September 2022 was 3.6%. (Note that this rate jumped to 5.2% by December of 2022.)

While complete principles of the calculation of the GRAT’s gift tax value are outside of the scope of this presentation, we get there using principles set forth in IRS Publication 1457. We are directed to use term-certain factors from IRS Table B (2000CM) prior to 2023, or Table B (2010CM) for 2023 and after. We use these terms to calculate the present value of the retained annuity interest, which is then subtracted from the value of the initial transfer to the GRAT itself in order to determine the gift tax present value of the remainder.

In Table B (2000CM), the annuity factor for a 2-year GRAT, using the 7520 rate of 3.6%, is 1.8970:

(Note how this same factor is higher, 1.9024, for a 7520 rate of 3.4% - illustrating how, as the 7520 rate increases, the present value of the annuity decreased which in turn increases the gift tax present value of the remainder interest.)

So, this brings us to the optimal annuity payment. Baked into this annuity factor is the assumption of growth at least equal to the 7520 rate of 3.6%. So, what if we went with an annuity of 50% of the initial transfer, or $607,000? If we multiply that amount by our annuity factor we get:

$617,500 x 1.8970 = $1,171,397.50 (present value of annuity)

So, the present value of the remainder, which is our gift amount, will be the initial fair market value of the GRAT ($1,235,000) minus the present value of the annuity ($1,171,397.50), we get a gift amount of $63,602.50.

Where the real magic happens is in exploring the growth of this trust, and the remainder. On the first anniversary of the GRAT (September 30, 2023, see Treas. Reg. 27.2701-3(b)(3)), it fell on a weekend meaning we must average highs and lows from September 29 and October 2, respectively. For these, we get $44.14 and $43.31 on September 29, averaging to $43.73 for that date, and $45.17 and $43.86 on October 2, averaging to $44.52. These amounts further average to $44.12 on September 30, giving us a GRAT value of ($44.12 x 1,000 shares) = $4,412,000. (Note that no dividends were indicated during that time from historical data). Our GRAT has almost quadrupled in value for the first year.

Source: Yahoo.com

In order to satisfy our annuity amount of $617,500, we would divide that amount by our per-share price of $44.12 to yield a distribution of 13,996 shares to be distributed to the grantor. That leaves us with 86,004 shares for a remaining GRAT value of $3,794,496.48.

Then, the following September 30 (2024), the final annuity payment will due. At the time of this writing (August 20, 2024), NVIDIA is trading at $127.00 per share – giving us a current GRAT value of $10,992,508. If this trading price held level through September 30, 2024, then after netting out the annuity of $617,500, we would be left with a remainder of $10,305,008.

In other words, we used gift tax credit to shelter an initial gift of $63,602.50, which could grow (free of gift or estate tax) to more than $10,305,008 – a staggering amount indeed! But, there is a trade-off. If the grantor were to die today, then the lesser of this amount or the annual annuity divided by the 7520 rate (for the month of death, currently being August 2024) would be included in the gross estate. Given that this annuity calculation comes out to ($617,500 divided by 5.2% = ) $11,875,000, the grantor would have the entire FMV of the GRAT included in their gross estate.

Note also that this is an incomplete illustration. What if we had decreased the first-year annuity, and increased the second-year annuity by no more than 120% of the first year annuity? That could perhaps have gotten us closer to a zero gift tax value for the remainder.

And, what if we were to take the first-year annuity and place it into a new GRAT? Even more growth could be removed.

This strategy, of 2-year GRATs with each annuity payment being placed into a new GRAT, is known as a “rolling” GRAT strategy. Given the repetition of the term “GRAT value” in this section, perhaps a hint is in order as to a family who successfully deployed this 2-year rolling GRAT strategy to transfer significant growth of one of the largest American companies at a low gift tax cost to the next generation:

Source: Walmart.com

Who Should Consider a GRAT?

A GRAT is one of the neatest estate planning “tricks” there is under current law – especially given the ability (discussed above) to “zero out” the gift tax value of the GRAT. But, the shininess of the GRAT often leads to over-prescription of this planning technique. While this list is not all-inclusive, GRATs tend to work optimally in these situations:

Clients who are likely to outlive the selected GRAT term;

Clients holding portfolios of securities with high-growth potential, especially if the securities are easy to value;

Clients holding hard-to-value assets with high-growth potential, if the income generated is consistent enough to reliably pay the annuity amount;

Clients who have exhausted all, or significant portions, of their gift tax applicable exclusion amount(s);

Clients wishing to benefit their children primarily, instead of grandchildren (due to GST tax issues to be discussed below);

Clients not wanting to benefit charity with the transferred assets;

Younger clients, perhaps start-up founders, holding significant equity that could become publicly-traded; and

Perhaps most importantly, clients who are engaged with the process and willing to take on the maintenance requirements of the GRAT.

GRAT Pitfalls

To flesh out some of the points above, the GRAT is only as good as the maintenance thereof. GRATs must make distributions at least annually, and often use quarterly distributions. This requires oversight as to when distributions should be made, and in what amounts. While the grantor can be trustee, they will often need assistance from an investment advisor as to the amount and timing of distributions of securities in-kind. This gets amplified where a client chooses to “immunize” the GRAT, meaning that significant early success in the GRAT is locked in through a substitution of volatile securities for more stable securities (such as bonds). While this can be done on either a calendar-year or fiscal-year basis, the calculations must remain consistent with the GRAT instrument itself.

While, as illustrated, there are significant gift tax discounts available for a GRAT, these discounts cannot be applied in the same manner for purposes of the generation-skipping transfer (GST) tax. GRATs are usually subject to an estate tax inclusion period (ETIP), meaning that GST exemption cannot be allocated to the GRAT until the end of its term. The outcome, if the GRAT is successful, is GST allocation to a significantly-appreciated remainder distribution from the GRAT. For that reason, it is often recommended to elect out of automatic allocation and instead distribute the GRAT remainder to a trust that will remain non-exempt from GST tax.

And, on all of these points, the success of a GRAT depends on accurate tax reporting and valuation. A gift tax return (Form 709) should be filed for the year in which the GRAT is funded, reflecting both the fair market value of assets transferred to the GRAT and the calculation of the present value of the grantor’s retained interest. On this or a subsequent gift tax return, an election out of automatic allocation of GST exemption for the GST portion of the GRAT is needed as well. This latter point is often forgotten or neglected.

Conclusion

Where properly deployed and maintained, the GRAT can be an excellent vehicle to accomplish our general goals of freezing, squeezing, and burning estate assets. However, care must be taken in identifying appropriate assets, balancing asset choice with the goldilocks zone of a term and annuity amount, properly reporting transfers to the GRAT, and properly reporting and maintaining the GRAT (including timely distributions). While the GRAT works great for high-growth stock, such as NVIDIA illustrated above, it can be difficult to spot these winners for any investment purpose - much less for the specific purpose of funding a GRAT.

Note that this strategy is not for the faint of heart, either. If you are a practitioner, jumping headlong into GRAT preparation and implementation is not recommended without significant up-front learning about the various risks and choices. This article barely scratches the surface of basic requirements. Likewise, clients seeking this strategy should be well-informed about the risks, and their options, before implementing GRATs.