ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Tim Harden is a CPA with Gatto, Pope & Walwick, LLP who works with estates, trusts, and individuals to provide tax saving strategies and compliance services. He has an extensive background in the field of trust, estate, and gift tax, including the areas of probate, asset protect, and complex trust and estate planning with tax compliance, including roughly 16 years as an attorney in this area prior to changing his focus to public accounting.

Table of Contents

Example

Quincey Harker, III is the attorney of and executor for the estate of C. Earl Sarkany, an Eastern European immigrant and naturalized United States citizen who lived in suburban Metro Detroit with his now-widow Lucy Sarkany. Quincey and the accounting firm he hired have accumulated substantial fees, as well as having commissioned numerous real estate appraisals due to Mr. Sarkany’s fondness for acquiring American soil. The head estate accountant recently mentioned the “642(g) election” on their weekly conference call. Quincey is a capable estate lawyer, but he has always struggled with remembering Code Section numbers. In addition, he doesn’t work on that many taxable estates. Therefore, he has decided to thoroughly familiarize himself with this election so he can impress the accountants with his deep tax knowledge on the call next week.

His first question – what is this election?

Despite a niggling doubt, Quincey’s initial assumption is that the various expenses he and the other estate professionals have incurred to date, the administrative expenses, would be deductible on both the estate tax return (Form 706) and the estate income tax return (Form 1041). After all, there are two different taxes at play. Form 706 reports the estate tax liability under the Internal Revenue Code (the Code), and Form 1041 reports the income tax liability. Since they are two different taxes, deducting them in both places would not mean that they were being deducted twice against the same tax liability. Upon refreshing his memory on the matter, however, Quincey is abashed to discover that he was right to doubt his intuition. For an undisclosed reason, Congress felt that this scenario was not desirable and enacted Code Section 642(g).

Code Section 642(g) prevents double deductions. It provides:

Amounts allowable under section 2053 or 2054 as a deduction in computing the taxable estate of a decedent shall not be allowed as a deduction (or as an offset against the sales price of property in determining gain or loss) in computing the taxable income of the estate or of any other person, unless there is filed, within the time and in the manner and form prescribed by the Secretary, a statement that the amounts have not been allowed as deductions under section 2053 or 2054 and a waiver of the right to have such amounts allowed at any time as deductions under section 2053 or 2054. Rules similar to the rules of the preceding sentence shall apply to amounts which may be taken into account under section 2621(a)(2) or 2622(b). This subsection shall not apply with respect to deductions allowed under part II (relating to income in respect of decedents).

In addition to preventing double deductions, this Code Section sets the default rule that such administration expenses will be deductible under on the Form 706 unless an affirmative election to the deduct the expenses on the Form 1041 is made by means of a filing with the IRS.

What expenses does the election apply to?

Quincey’s concern turns to the type of deductions that this applies to, because sometimes the Code can be unclear and need significant interpretation. He is relieved to see that the expenses at issue are listed in Treas. Reg 20-2053-3: executor’s commissions; attorney’s fees; and miscellaneous expenses. “Miscellaneous expenses” include such expenses as: “court costs, surrogates’ fees, accountants’ fees, appraisers’ fees, and expenses incurred in preserving and distributing the estate”. He realizes that this is where the possible double deduction arises. For estates and non-grantor trusts, Treas. Reg. 1.67-4 states that costs “that are paid or incurred in connection with the administration of the estate or trust that would not have been incurred if the property were not held in such trust or estate.” All the above listed expenses could qualify under this Regulation, because they are all fees that would be incurred as costs of administering the estate.

Similarly, administration fees including attorneys’ fees, court costs, trustee fees, accountants’ fees, and similar are available to an estate to deduct from the gross estate under various Regulations, including 20.2053-1, 20.2053-2, 20 2053-3, 20.2053-6, and 20.2053-9. Other fees are listed as well, but they clearly fall in the same category of expense as contemplated by the Regulation pertaining to the expenses deductible for estates and nongrantor trusts. One notable exception is that funeral expenses are deductible against the estate tax, but they are not available as an income tax deduction.

This comparison makes it clear to Quincey what Section 642(g) applies to, even if he is still unsure why they enacted it in the first place. Next, it is necessary to turn to the question of who can make this election.

Who can make the election?

Estates and trusts would seem to be the obvious answer to this question to Quincy, and this time he is right. However, he is surprised to learn that this was not always the case. The current wording of Code Section 642(g) contains the phrase “…shall not be allowed as a deduction…in computing the taxable income of the estate or any other person” (emphasis added). The italicized section was added in response to a Tax Court case called Commissioner v Burrow, which held that some of the same items were able to be deducted both on the estate tax return and the trust income tax return. The court read the statute to only apply to an “estate,” although in the case of a testamentary trust, it would be possible to argue that the estate should encompass the testamentary trust as well. Congress enacting a change to the law eliminated this potential area of dispute.

Even though it is pretty clear that under today’s law, Code Section 642(g) applies to both estates and trusts, Quincey does pick up on a pretty important distinction based on his own situation. It is possible that the executor of the estate responsible for filing the estate tax return and the trustee of the trust that could deduct these expenses are different people. He is the executor of the estate and will be signing the estate tax return, but the widow Lucy is going to be trustee of the trusts established in the estate administration. And his fact pattern is far from the only scenario where such a disunity could arise. The only limit is the creativity of clients naming fiduciaries in their estate plan documents. In this scenario, if the executor were to choose to deduct the expenses on the estate tax return, it could be a detriment to the beneficiaries of the trust, which could cause difficulties for the trustee.

He realizes that the best course of action will be for him as the executor and Lucy as the trustee to work together as best they can in making this decision. Hopefully, the awareness of the potential for conflicts would facilitate cooperation. In addition, seeking the buy-in from all the relevant beneficiaries would be helpful, especially if they were willing to agree to any proposed election.

How is the election made?

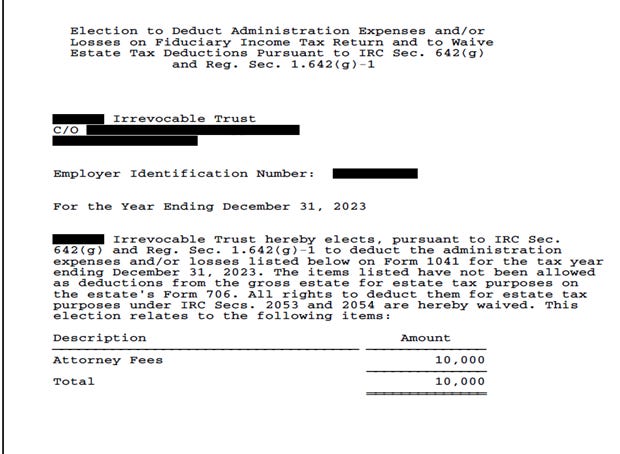

Quincey breathes a sigh of relief when he reaches this point. This whole process was a lot more complicated than he thought it would be, but this part seems pretty straightforward. Making the election is done by filing a statement with the estate’s income tax return for the year. It is important, he notes again with interest, because if no election is made, these expenses are only deductible on the estate’s 706. Most tax software will have an input to generate the statement. Here is a sample of what a statement might look like, for informational purposes only:

Generally, the statement will be filed with the 1041 for the estate, but it can also be filed with the district director for the district in which the return is filed. Importantly, the election statement must be filed before the statute of limitations for that tax year expires.

Then Quincey discovers a wrinkle. The election is irrevocable, so caution is warranted before making a final decision. It is the combination of the above two factors that gets Quincey thinking. The statute of limitations ends three years after the filing of the estate tax return, so the executor will have at least three years and nine months to make an election. However, for a 1041, the statute of limitations ends three years after the filing of the return that is due in the year following death, giving the executor four years, four months, and fifteen days to make the election on the 1041.

Therefore, it makes sense to him that delaying the election as long as possible would be prudent. This is especially true since deductions used for income tax purposes must be used in the year they occur, as opposed to estate tax deductions, which go on the 706 whenever it is filed. Further, it should be noted, as shown on the sample notice above, the election is not all or nothing for all expenses. It is possible to choose certain expenses to be deducted on the 706 and others on the 1041, as long as they are specifically identified on the election.

One further wrinkle here that he uncovers is that there is a difference in what deductions could be reported on each return. On the 706, it is permissible to estimate the post-filing executor’s commissions, attorney’s fees, and CPA/appraisal fees and still take them as a deduction. However, on a 1041, the deductions will only be those paid out for the applicable year on a cash basis (since accrual most likely would not apply to the estate). Therefore, the possibility exists that a larger deduction could be taken on the 706 than on the 1041.

A final practical pointer, he discovers, would be to use the deductions on the 1041s during the period of consideration in order to have as much time as possible to make the election, since that statute expires later. In this case, the election would not be made with the 1041, but would be filed separately with the district director for the district where the return was filed before the expiration of the statute of limitations.

Should He Advocate for Making the Election?

Now that he understands what the election is and how to make it, Quincey turns to whether it should be made. He really wants to seem like he knows what he is talking about when he discusses this with the accountants, so he tries to reason his way through the possibilities. Despite this, he quickly realizes that, as with most tax-related questions, there is not a one size fits all answer. Instead, there are several competing considerations.

First is the question of whether there will be an estate tax at all due to the marital deduction. If Mr. Sarkany had left his entire estate to Lucy, then the unlimited marital deduction would zero out the estate tax, at least until Lucy’s death in the future. In that scenario, then it would make sense to take the deductions on the 1041, since there would be no estate tax to offset. However, in this case Mr. Sarkany left a QTIP trust for Lucy that qualifies for the marital deduction, but he also made specific bequests of certain real estate properties to relatives, the total of which are in excess of his exemption amount. Therefore, there will be some potential estate tax that could be offset with deductions.

Second is another technical issue with regard to types of gain that could be realized. Everything included in the taxable estate will receive a step up in basis. This means that there will be minimal income tax to the estate upon the sale of assets, and therefore taking the deductions against the estate tax would be more beneficial. However, there are two other scenarios that where that might not be the case. First, if the assets are held for a long period of time before distribution, perhaps because of an estate dispute, then they might appreciate enough that their sale will cause significant taxable income. Second, there is the possibility of so-called Kenan gain. This kind of gain can occur if two conditions are met: (1) whether because of a formula clause or a specific bequest, the estate has to pay a specific amount of money or transfer a specific property; and (2) the estate satisfies this obligation with different property. For example, if Mr. Sarkany’s trust had a specific bequest of Real Property A to a nephew, but instead the executor satisfied it with Real Property B, to the extent that Real Property B is appreciated property, the estate will realize gain on the transfer. Therefore, in either of these latter two scenarios, it may make sense to take the deductions on the estate income tax returns.

Third is the time value of money. For example, if estate tax is deferred under Code Section 6166, it may be more valuable to take the deductions on the income tax return. That is because the income tax would be due sooner than the estate tax in that scenario.

Fourth, the difference between the estate tax and income tax rates is important. If one is higher, than a deduction against that one would be more valuable.

Fifth is whether the deduction would help save AMT in either scenario.

Sixth is the consideration of funding formulas in the estate planning documents. For example, if estate taxes where allocated to the residue, taking this deduction on the income tax return would increase the estate tax and decrease the residue. This could be potentially upsetting to the residuary beneficiary.

In summary, it is a complicated question. However, the best practice, and his plan, is to run the numbers in the various scenarios that could unfold so that the impact of making the election is clear. In addition, he will carefully consider the various parties involved. In particular, Lucy is formidable, and he will have to be ready to explain his thinking to her, whatever decision he makes. Further he must consider the party or parties who would benefit from taking the deduction on the estate tax return against the beneficiaries who would pay increased income taxes. He is not entirely sure if they will be different, but if they are, he will have to weigh their interests against each other.

At this point, Quincy feels good. He has a solid understanding of this election now, and even though he needs more information to give a firm recommendation, he is ready for the call with the accountants. For the time being, he will fall back on the classic lawyer answer: it depends.