Mismatches in the Remaining Gift Tax Basic Exclusion vs. GST Exemption

What causes one to be greater than the other?

Table of Contents

Intro

Today’s question is a fairly simple one, but with fairly complex downstream implications.

What causes the remaining GST tax exemption to be greater than the remaining gift tax basic exclusion amount, or vice versa?

As always, the intent of this article is not to give you the complete answer with all possible permutations, but instead to highlight common answers at the top of the bell curve with the goal of helping you to be a better issue-spotter.

Comprehensive tax and financial planning for an individual or family often includes tracking the amounts of these exemptions that are used, versus what remains. And the tracking does not always tell the entire story nor is it always readily apparent from documents available. While the prime source for this information might be prior gift tax returns (Form 709), it is possible for GST exemption to be allocated without being required to file such a return. It may also be the case that no 709 is actually filed when required, yet a gift used gift tax basic exclusion or GST exemption.

Before diving in, however, a basic lesson on the “use” of these exemptions is in order. The gift tax basic exclusion and GST exemption are each currently pegged to the estate tax basic exclusion amount, which for 2025 is $13,990,000 for each U.S. citizen or resident. This has not always been the case, however, as at various times in their respective histories the gift and GST tax exemptions were not unified with the estate tax applicable/basic exclusion.[1]

Gift tax basic exclusion is not actually used dollar-for-dollar, but instead is applied as applicable credit against gift tax on a cumulative basis (as recalculated for each year that gifts are made). This “use” occurs after reductions for gift splitting elections, any annual exclusions, and marital and charitable deductions (the net being the “taxable gifts”), and there is no ability to elect to pay gift tax in lieu of using the basic exclusion. Further, for a widower who has received a deceased spouse’s unused exclusion (DSUE), the DSUE must be used first as applicable credit before dipping in to the basic exclusion.

Taxable gifts are calculated on a gift tax return, but a failure to file does not prevent the IRS from later asserting that taxable gifts might have occurred for a non-filing year and, as we will discuss below, it does not stop the IRS from adjusting the value of gifted assets on audit thus using more basic exclusion. No gift tax is paid until the DSUE (if any), then the basic exclusion, are used completely for cumulative lifetime gifts – and even then the inflation adjustments to the basic exclusion each year may create additional gifting room if in any given year the basic exclusion is exhausted.

For GST tax exemption, it too has a storied history. Completed gifts to irrevocable trusts prior to September 26, 1985, and direct gifts prior to October 23, 1986, are generally not subject to GST tax. GST exemption was traditionally used by being “allocated” on the appropriate schedule of Form 709 (now called an “affirmative” allocation), and in many contexts such an outcome is still recommended even if the 709 does not have to be filed. But, for transfers to irrevocable trusts that are classified as “GST trusts” after December 31, 2000, automatic allocation of GST exemption can occur regardless of whether or not Form 709 is actually filed. However, if the trust is not a GST trust, GST exemption still must be affirmatively allocated on Form 709. Further, if a trust is subject to an estate tax inclusion period (ETIP), no allocation (automatic or affirmative) of GST exemption takes effect until (1) the termination of the ETIP (based on the value of the trust at that time), or (2) a taxable distribution to a skip person during the ETIP (and then only to the extent of the value of the distribution itself).

This allocation of GST exemption, unlike use of gift tax exclusion, does not result in a tax credit. Instead, it reduces the GST tax rate to as low as 0% by comparing, dollar-for-dollar, the taxable gift portion of the trust to the GST exemption allocated. A perfect dollar-for-dollar allocation creates an inclusion ratio of zero, which creates the 0% GST tax rate, while no allocation means an inclusion ratio of one and a GST tax rate of 40% (under current law, as the GST tax rate is the highest estate tax rate at the time of a GST transfer).

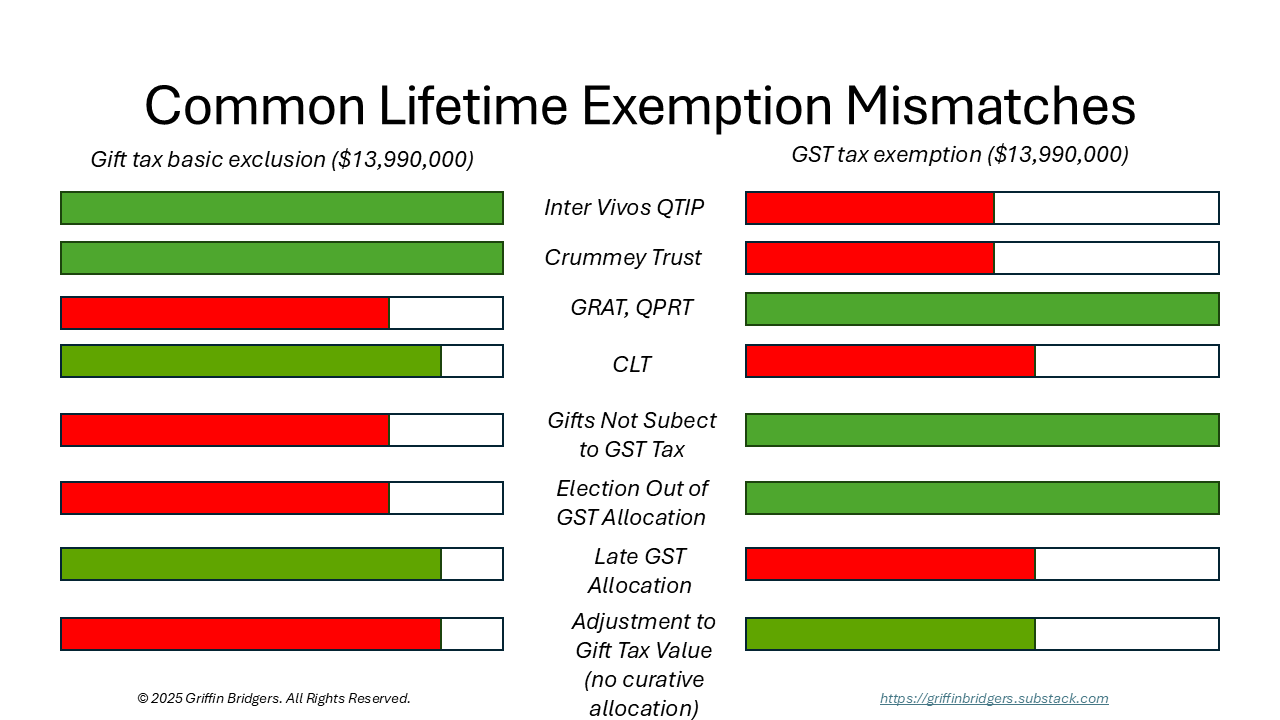

Having considered these contexts, let’s explore some situations where use of these exemptions might not be unified or concurrent. To summarize, here is a quick graphic which hopefully aids your understanding - note that the amounts in the meter bars are not intended to be accurate depictions but instead vary based on general differences you may encounter:

ETIP and QTIP Trusts

Given the rules just discussed, it is common to elect out of automatic allocation for trusts subject to an ETIP. One exception to this rule is a trust for which a QTIP election is made, in which case the reverse QTIP election (if made) allows the donor to allocate their GST exemption to the trust (as opposed to requiring the beneficiary spouse to use theirs as a function of transfer tax ownership under IRC Sections 2044 or 2519).

So, our first example would be an inter vivos QTIP trust with a reverse QTIP election. In such a case, no gift tax basic exclusion would be used for QTIP-elected assets because this election creates a gift tax marital deduction. But, the donor would still allocate their own GST exemption to the QTIP-elected assets – resulting in use of GST exemption without use of gift tax basic exclusion.

Keeping with the theme of trusts subject to an ETIP, we often find certain retained-interests trusts – namely the grantor retained annuity trust (GRAT) and the qualified personal residence trust (QPRT) – as common candidates. These trusts are usually subject to a time-value-of-money discount on the gift tax value of the remainder interest, as the grantor’s retained interest is not subject to gift tax (since it is technically a “gift” to themselves). But because of the operation of the ETIP rules with respect to the GST exemption, it is common to elect out of automatic allocation of GST exemption since the allocation would be based by the (presumably higher) remainder value of the trust, without time-value-of-money discounts, at the end of the trust’s term (or, if earlier, at the death of the grantor).

As a result, with a QPRT, it is common to see use of gift tax basic exclusion amount without corresponding use of GST exemption. The same holds true with a GRAT, although many GRATs are designed to be “zeroed out” for gift tax valuation purposes (based on the time-value-of-money discount) meaning they use little if any gift tax basic exclusion.

The allocation of GST exemption is not typical for charitable remainder trusts, as it is rare for anyone other than the donor (and perhaps their spouse) and qualified charities to benefit from such a trust. For non-reversionary charitable lead trusts, however, GST exemption may be allocated for the remainder beneficiaries but with a twist – additional GST exemption must be allocated based on the assumed interest crediting to the trust itself during the term of the charity’s income interest. This results in disproportionate use of GST exemption where, like with a GRAT, there may be little or no use of gift tax basic exclusion for the gift of the present value of the remainder interest.

Crummey Trusts

Transfers to trusts that qualify for the gift tax annual exclusion – including transfers subject to Crummey withdrawal rights, and certain other trust transfers described in IRC Sections 2503(b) and 2503(c) – naturally will not use gift tax basic exclusion (also sometimes known as the “lifetime” exclusion) since the basic exclusion only applies to taxable gifts (which are net of annual exclusions, deductions, and split gifts as mentioned above).

There is also a GST tax annual exclusion (by operation but not by name), in the form of a zero inclusion ratio that applies to the “nontaxable” portion of a gift (i.e., the portion that qualifies for the gift tax annual exclusion). But where transfers in trusts are concerned, Crummey withdrawal rights do not qualify for this “GST tax annual exclusion” unless they meet very specific requirements that are rarely met. These requirements, set forth in IRC Section 2642(c) for withdrawal rights held by skip persons (and in Treasury Regulations for non-skip persons) require that the lapsed portion of a Crummey power must (1) be held in a separate share trust for the sole lifetime benefit of the powerholder, for which (2) the assets will be included in the powerholder’s gross estate at death. In such a case, “use” of GST exemption is shifted to the powerholder and applies at their death.

For all other forms of Crummey power not meeting this definition – including lapsed portion(s) thereof that meet the requirements of IRC Section 2514(e) – GST exemption of the donor must be allocated in order to maintain an inclusion ratio of zero (i.e., complete exemption from the GST tax) for the trust. In other words, even though no gift tax basic exclusion amount is used for the Crummey powers, GST exemption gets allocated to them unless the power meets the 2642(c) exclusion above. Even then, this can result in a certain “wasting” of GST exemption as the unlapsed portions of Crummey powers (and sometimes growth thereof) will be subject to re-allocation of a powerholder’s GST exemption at death by virtue of holding the power of withdrawal, or a power of appointment over an incomplete gift, at that time.

These allocations may be automatic, even if no 709 is filed, for transfers subject to Crummey powers that occur after December 31, 2000. For Crummey powers created on or before that date, Rev. Proc. 2004-64 may allow for a late filing if no 709 was filed to allocate GST exemption. However, late election relief after that date may require either (1) a late allocation as discussed below, or (2) a private letter ruling if a return is filed but not amended within 6 months, assuming all qualifications for relief are met.

Gifts Not Subject to GST Tax

The GST tax generally only applies for gifts (or transfers at death) to, or for the benefit of, skip persons. Skip persons are individuals who have a generation assignment (based on family tree or age difference) of two or more generations below the transferor. Skipping generations above the transferor (upstream planning) does not, however, lead to GST tax because of the assumption that wealth moves downstream.

This means direct gifts to non-skip persons (the highly technical and artful term given to anyone who is not a skip person under IRC Section 2613(b)) won’t use any GST exemption, but may use gift tax basic exclusion to the extent any available annual exclusions are exceeded.

Where transfers in trusts are involved, GST exemption does not have to be allocated. In fact, doing so may be inefficient if the trust will not benefit at least one generation of skip persons. While GST exemption can be allocated based on GST “potential” (i.e., the likelihood that unborn future or remainder beneficiaries might be skip persons if the trust continues or is distributed for their benefit), it is not mandatory. If no 709 is filed, automatic allocation might apply assuming the trust is a GST trust. But if the donor files a 709 to elect out of automatic allocation, it may be the case that gift tax basic exclusion gets used while no GST exemption gets allocated – again creating a mismatch.

Faulty or Late Allocations

GST exemption can be allocated at any time up to the due date (with valid extensions) for filing the estate tax return (Form 706) after the death of a donor. But where there is no automatic allocation on the 709 during life, this can create mismatches. Likewise, where there is an intent to elect out of automatic allocation but this election is not made (and not fixed), there can be mismatches as well.

Let’s take the prior point (on a lack of living skip persons), where perhaps an ILIT was created for children and their future descendants who are unborn at the time of the creation of the trust. The ILIT purchases a convertible term policy, and annual exclusion gifts of premiums are made to the trust. The donor elects out of automatic allocation, and no 709s are ever filed. As the end of the term approaches, the donor contemplates exercising the conversion feature – and at that time some grandchildren have been born (who will be remainder beneficiaries of the ILIT). In the year before conversion, the donor decides that perhaps the use of their GST exemption is now wise and chooses to affirmatively allocate their GST exemption at that time. Is that permitted?

The answer is yes, but the GST exemption allocated will be based on the value of the ILIT assets at the time of allocation (which may be the first day of the month in which a 709 is filed to make such allocation). This may result in a better outcome if the value of the policy at the time for gift tax purposes is less than the cumulative premiums to which GST exemption might have been allocated over the term of the policy. But, this also means GST exemption is being used where no gift tax basic exclusion was used since the late allocation relates back to one or more previously-completed annual exclusion gifts.

On the other hand, let’s say a gift is made to an irrevocable trust. The donor gifts closely-held business interests while taking an aggressive valuation discount of 75%. A 709 is filed to report the value of this gift, and the donor affirmatively allocates GST exemption based on this discounted value while electing out of automatic allocation (for that year and all future years). The IRS audits the gift tax return within the limitations period, and successfully reassesses the value of the gifted assets, resulting in the use of more gift tax basic exclusion (and perhaps payment of gift tax as the incentive for audit to begin with). But at the same time, there may be no allocation of GST exemption to the adjustment in gift tax value itself due to the prior rigid affirmative election, and a late election based on the current adjusted value may be required (which won’t be enough to cover the entire trust if the gift tax basic exclusion was exhausted). Again, this can create a mismatch. A similar outcome might occur in the case of a formula gift clause.

A Bonus - Use of DSUE

As discussed above, DSUE preserved for a surviving spouse must be used first to offset gift tax before applying basic exclusion. This was not illustrated in the image above, because doing so would require a graphical representation of a “super” gift tax applicable exclusion which would not align with the other elements.

However, it is important to note that a portability election does not preserve a deceased spouse’s unused GST exemption.

For this reason, merely having DSUE almost always means that there is a disparity between a surviving spouse’s available gift tax applicable exclusion versus their available GST exemption - regardless of whether or not any lifetime gifts have even been made by the surviving spouse (another reason why it was not illustrated above and is labeled as a “bonus”). And as long as DSUE is available, it means GST exemption could get exclusively burned off for lifetime gifts without corresponding reduction to the gift tax basic exclusion amount itself, depending on variances for types of gifts and corresponding elections (or lack thereof) as highlighted above.

Conclusion, and Downstream Effects

Obviously this article does not cover all possible permutations of where the gift tax basic exclusion amount and GST exemption might not be used dollar-for-dollar in tandem, nor does it completely portray the options that might be available to achieve or avoid such an outcome if it was not intended. But, these are common outcomes encountered where varying forms of lifetime gifts – whether in trust or direct – are made.

This mismatch can have trickle-down effects at the death of a donor. Many formula clauses in documents, or even the ability of a spouse to disclaim or for an executor to make partial QTIP elections, can be driven by the remaining basic exclusion amount and GST exemption not used for lifetime gifts. For example, if there is more remaining basic exclusion than GST exemption, this can result in the creation of a credit shelter trust which is partially non-exempt unless affirmative action is taken to divide such trust into exempt (inclusion ratio of zero) and non-exempt (inclusion ratio of one) shares. If GST exemption exceeds remaining basic exclusion, this can have a similar downstream effect on a marital trust in terms of exempt/non-exempt shares.

Note too that we did not cover state estate, death, and inheritance taxes – which may have their own exemptions and which may extend to create state-level GST taxes at least at death. (Only one state – Connecticut – currently imposes a gift tax.) These are topics to cover in separate articles, but it is worth noting that these can further complicate the funding formulas described above.

As greater attention is shifted to transfer tax planning, questions from clients are sure to arise regarding differences between their available gift tax exclusion and GST tax exemption. Arming yourself with the knowledge to examine their plan and adequately answer these questions can be a great value-add.

[1] This article focuses on “basic” exclusion as this is the formal definition now given to the $13,990,000 inflation-adjusted unified amount for federal gift and estate taxes under current law. Prior to the enactment of the portability election, this was called the “applicable” exclusion. Since the onset of portability, the applicable exclusion is generally defined as the sum of (1) the basic exclusion, (2) deceased spousal unused exclusion (DSUE) of the most recently-deceased spouse, and (3) DSUE of previously-deceased spouses that is actually used for lifetime gifts.