Table of Contents

Background

On July 4, 2025, President Trump signed the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA). The OBBBA had the effect of making some sweeping changes to tax law, while also extending some of the provisions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA).

There are several sources out there that have dissected and analyzed the OBBBA ad nauseum. This article and my subsequent coverage will not be another repeat of this pattern. Instead, over the coming months, I plan to cover various aspects of the changes in isolation. It should come as no surprise that the natural starting point will be the changes to the estate/gift/GST tax basic exclusion amount.

This change represents a medium between two extremes in the anticipated possibilities of outcomes. On one extreme was the sunset of the TCJA, which would have sent the basic exclusion amount back to an inflation-adjusted base of $5,000,000. On the other extreme was a wholesale repeal of the estate tax (perhaps coupled with a replacement, such as a deemed disposition tax and/or elimination of the basis adjustment under IRC Section 1014 at death). Neither happened.

But instead of wholesale repeal, this change does (in a sense) bring a slow death to the estate tax, assuming the law remains unchanged. Let’s explore how, against the backdrop of the idea that the modern basic exclusion amount has never decreased and appears unlikely to decrease.

The New Basic Exclusion Amount

The change in law updates IRC Section 2010. Like many Code Sections, the TCJA baked in a combination of permanent language, which was superseded by temporary language (that would no longer be effective after 2025). Once the temporary language was no longer effective, the previously-superseded permanent language would then take effect again.

We found the permanent language in IRC Section 2010(c)(3)(A), which provided (under pre-TCJA law):

For purposes of this subsection, the basic exclusion amount is $5,000,000.

However, the temporary language of IRC Section 2010(c)(3)(C) added by the TCJA provided:

In the case of estates of decedents dying or gifts made after December 31, 2017, and before January 1, 2026, subparagraph (A) shall be applied by substituting “$10,000,000” for “$5,000,000”.

In other words, for the years 2018-2025, the base amount of the basic exclusion was doubled to $10,000,000. Or, perhaps we can view this as an increase to the base amount of $5,000,000.

This brings us to the current iteration under the OBBBA, which further increases this base by $5,000,000. The temporary TCJA language of IRC Section 2010(c)(3)(C) is removed, and the permanent language of IRC Section 2010(c)(3)(A) has been updated to provide:

For purposes of this subsection, the basic exclusion amount is $15,000,000.

Of course, we cannot stop there. The one element of this Code Section not directly changed by the TCJA was an annual cost-of-living adjustment to the basic exclusion amount, which was found in IRC Section 1(f)(3) (which itself was changed under the TCJA). This adjustment, mandated in IRC Section 2010(c)(3)(B), called for annual adjustments in increments of $10,000 (rounded) based on this cost-of-living adjustment, dating back to 2010.

Now this is where things get interesting, but they were always interesting to begin with. This adjustment was the product of the Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization, and Job Creation Act of 2010. It was made permanent at the end of 2012 by the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012, prior to which another “sunset” of the basic exclusion amount had been expected. What made this interesting was that the cost-of-living adjustment, starting in 2012, related back to the base year of 2010.

We won’t get into the mechanics of this, other than to point out that the new law under the OBBBA updates this base year from 2010 to 2025 but for inflation adjustments to the basic exclusion amount commencing in 2027. Some have pointed out this supposed “oddity,” but really it is consistent with how the Code Section was previously worded around adjustments to a year-one base. That being said, there could be some minor effects (beyond my limited and ever-fading mathematical and economic knowledge) on how these adjustments are calculated moving forward.

Effective Year

The OBBBA has some tax changes that do not take place until 2026, while others are effective for the current year of 2025. The increase to the basic exclusion amount will not be effective until 2026, so anyone who dies or makes gifts this year will have the same $13,990,000 basic exclusion amount that we had under the TCJA. Likewise, this same $13,990,000 basic exclusion serves as the GST tax exemption (by reference to IRC Section 2010(c) under IRC Section 2631(c)), with an increase in this exemption to $15,000,000 also taking effect in 2026.

Starting in 2027, this $15,000,000 base as noted above will be subject to cost-of-living adjustments. Without getting into the calculation of this adjustment or the accuracy of predicting it, here is where we get into the central premise of this article. If the new language of IRC Section 2010(c) remains unchanged, will the estate tax effectively repeal itself over time?

The Power of Compounding

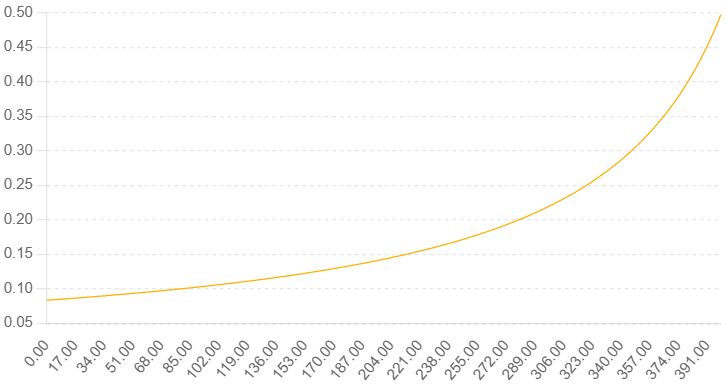

Many of us are accustomed to hearing about the wonders of compound interest, or compound growth. This growth is not constant or guaranteed, but it trends upward over time with the effect of eventually creating a “hockey stick” effect where the slope of the line continues to progress from mostly-horizontal to mostly-vertical.

This image illustrates the general concept:

Before diving in, it is important to note that the rate of growth impacts the slope of this line and how it develops over time. Higher growth rates accelerate the curve, but nonetheless growth-driven curves eventually reach vertical. While it has been over 25 years since I took Calculus, the concept of limits come in as well. But for purposes of our illustration, there is another factor that can accelerate this curve – an increase to the starting (or base) amount being adjusted. (And for those of you who are experts in this stuff I know this is overly-simplified and may not illustrate the economics or reality of compounding perfectly, so please read this with an eye of avoiding the urge for a “gotcha” moment.)

This brings us to the basic exclusion amount. If it continues to have inflation adjustments, it will eventually trend vertically-asymptotic. This outcome becomes, in effect, a functional repeal of the estate and GST tax.

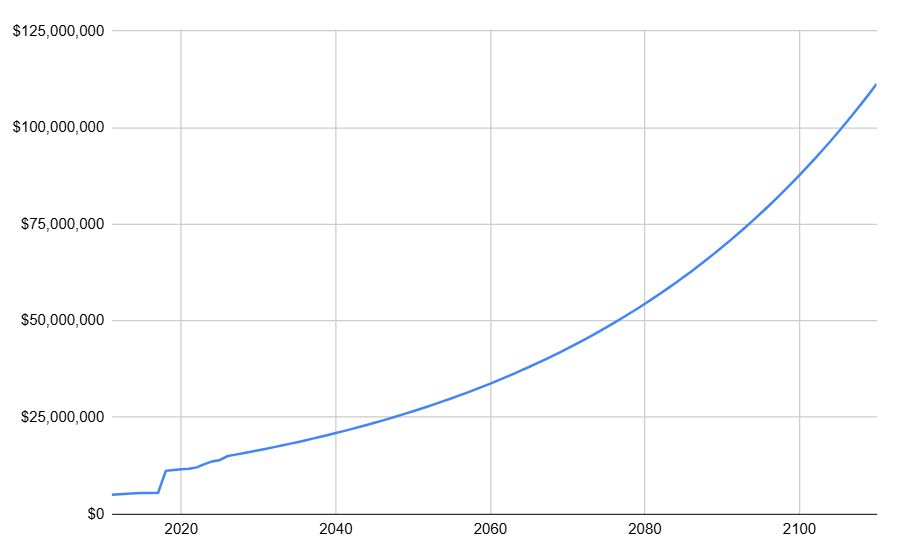

Again, while overly-simplified, I took the average annual increases to the basic exclusion amount since 2011 and plotted them out in a further projected chart to illustrate where the basic exclusion amount might be in the year 2110 (100 years after the original $5,000,000 base amount and annual inflation adjustments were added to IRC Section 2010). This simple formula projected an exclusion of $111,327,903 in 2110. Here is the chart:

Giver’s Regret?

Proactive planning to save future estate taxes has long been considered a dying skillset (pun intended), due to the ever-shrinking percentage of U.S. citizens and residents who are actually affected by the estate tax. While the specter of the sunset of the basic exclusion amount gave a temporary “boost” to demand for this skillset, we are now left with the settling dust of those who have made permanent wealth transfers with the motivation of avoiding an outcome that (for now) will not occur.

So, we are faced with the existential question surrounding all gifts that have the benefit of hindsight – was it necessary? This is where it becomes important to highlight the tax and non-tax benefits of lifetime wealth transfers. Subjects like decanting, modification, choice of situs, and use of trust protectors/trust advisors will increase in the coming months and years. And if you thought estate and GST tax were challenging subjects to navigate, then I must remind you of the admonition of Bachman-Turner Overdrive – You Ain’t Seen Nothing Yet.

Simple math dictates that gifts to completed gift trusts were worth it so long as (1) the compound growth curve outpaces the growth curve of the basic exclusion amount above, and (2) this (hopefully excess) spread in compound growth does not get pulled back into the taxable estate. But as many of my esteemed colleagues have pointed out, one cannot consider estate tax in a bubble. Income tax must be considered as well, and this compound growth cannot apply to the income tax basis of gifted assets without either (1) recognition of gain, or (2) gross estate inclusion for non-IRD assets. Swaps with grantor trusts will become an important subject as well, and as I have noted in recent articles these can be fraught with peril.

Remember, too, that GST tax leaves fingerprints. Most trusts have deferred GST tax reporting obligations, and (if things were not done right in the past) deferred GST tax liability. If you are looking for a tax skillset that will have utility, check out my vast offerings on YouTube and on this newsletter on GST tax and its evil cousin – Crummey powers - along with grantor trusts.

It is also important to note that the human element affects these outcomes. People do not behave rationally, so the rationality of the charts and projections above ignore consumption (whether it is for one’s own benefit, or given away to individuals or charities). Now more than ever, the human touch is needed - especially in estate and wealth transfer planning, and especially where multiple parties with differing expectations are involved in a wealth transfer.