An Intro to Trustee Distribution Powers

Understanding the gatekeepers of property leaving a trust

This is a continuation of the series on everything you ever wanted to know about estate planning trusts. For an intro and index to this series, please click here. The linked article will have a series index that gets updated periodically as well, so please bookmark it.

Table of Contents

Intro

A recurring theme over the introductory articles in this series on trusts has been the power to put property in, and take property out, of a trust. To recap, revocability of a trust is often explored through the lens of whether a settlor can take back their contributions to the trust. Beneficiaries may have a power to take property out through a power of appointment. (What we have not yet discussed is that beneficiaries should refrain from putting their own property into a trust, unless the trust is structured a certain way and possibly administered in one of a handful of certain states.) But, as mentioned, the ultimate power to remove property from a trust often lies with trustees. Outside of powers of revocability, or powers of appointment, trustees often are first in line to determine if and when property leaves a trust. This property leaving trust is often assigned the tag of distribution.

The bounds of a trustee’s distribution power are often spelled out by the trust instrument, which may be supplemented or even superseded by applicable law governing the administration of the trust. For example, a trustee who is also a beneficiary under a trust instrument may be limited under state law by how much they can distribute to themselves so as to prevent the conversion of their (self)-distribution right into a lifetime general power of appointment. (See, for example, Colorado Revised Statutes Section 15-1-1401.)

But, in any case, the difference between a trustee’s power to take property out of a trust, and a settlor’s or beneficiary’s power to take property out of a trust under a right to revoke or power of appointment, involves the addition of fiduciary duties. This addition of fiduciary duties may happen even where there is no intent to add such duties. The outcome is a beneficiary, and possibly even a settlor (whether or not a named settlor) wearing the trustee “hat” and acquiring the fiduciary duties related to that hat for certain purposes.

We will discuss these fiduciary duties in greater detail in subsequent articles, but determining the scope of such duties often requires us to first classify the trustee’s distribution powers.

Property to which Distribution Power Relates

To understand distribution powers, you must first understand what portion of the trust correlates to the distribution power. A trust is made up of two components – principal (also sometimes called corpus), and income.

Principal is the property initially transferred to the trust by all settlors, along with any growth in value not yet converted to cash/other property or, if converted to cash or other property, not allocated to income by the trustee.

Income is the cash income earned by the principal. This is more of an accounting determination, focusing on traditional forms of cash income generated by property (rents, interest, dividends, profits distributions, royalties, harvested timber and crops, etc.). “Income” may also include the free use of property which, if not owned by the trust, would usually require a beneficiary to pay rent to the owner.

Appreciation in value, although treated as income for income tax purposes, is by default treated as principal under trust accounting principles. But, trustees in most states can elect to allocate appreciation in value that is actually realized or recognized for tax purposes (such as capital gains and extraordinary dividends) to income – sometimes for tax purposes, and other times to balance benefits between current and remainder beneficiaries as will be discussed below.

A trustee’s distribution powers are usually split between income and principal. Some beneficiaries may only have the right to distributions of income, or distributions of principal, while other beneficiaries might have the right to distributions of both.

Types of Trustee Discretion

In some cases, a trustee has the discretion as to whether, when, and how much income and/or principal to distribute – this is called a discretionary distribution power. In other cases, especially for income, the trustee may be required to distribute all or some portion of income or principal at certain times – this is called a mandatory distribution power and this type of power may lack trustee discretion (at least to the question of whether or not to distribute to begin with).

Even for a mandatory distribution power, however, the trustee may have the discretion to divide the distribution equally or unequally across multiple beneficiaries. This is often referred to as a sprinkle or spray power, and it can apply to both discretionary and mandatory distribution powers. Trustees may also have the power to decide which specific assets will be distributed to specific beneficiaries or even to subtrusts for specific beneficiaries, subject to certain fiduciary limitations (like the “fairly representative” standard to be explored in a later article).

As noted above, these forms of trustee discretion usually determine the scope of fiduciary duties. Simple word choices within a trust instrument can affect these fiduciary duties as well. For example, the use of “may” implies that a trustee can say yes or no to distributions, while the use of “shall” implies that a trustee must make at least nominal distributions (although, in some states,[1] “shall” by itself is interpreted as “may” unless the trust expressly adds context).

Discretionary distribution powers are often subject to guidelines for determining the needs of beneficiaries as well. This is often stated as an objectively-measurable standard, known as an ascertainable standard for tax (and sometimes creditor protection) purposes. Terms like health, education, support, maintenance, and welfare are considered objectively-measurable needs that can be part of this standard. But, terms like comfort and satisfaction are not objectively measurable and thus do not create an ascertainable standard. If a standard is not ascertainable, it may be challenging for a trustee to satisfy their fiduciary duties. And, if a beneficiary acquires the trustee hat, a standard that is not ascertainable can cause the beneficiary to have a general power of appointment – causing them to become the deemed owner of trust principal and/or income for property law and tax law purposes.

Even where there is an ascertainable standard language, there could be additional expansions and qualifiers. Distributions may also be capped for certain periods, or even the lifetime of a beneficiary, if the trust instrument specifically spells out a cap (usually expressed as a numerical amount, also called a pecuniary amount). Such pecuniary amount could be adjusted for inflation, or may be based on a different standard such as a beneficiary’s W-2 income. There could also be guaranteed distributions at different milestones such as finishing college, or special purpose distributions for purchasing a home, starting a business, or even a wedding. In a subsequent article, we will discuss some of the issues with these types of distributions.

Sometimes, however, a trustee may not be limited by an ascertainable standard. Such a trustee may have full discretion to make distributions of income and/or principal. For reasons we will discuss below, such a trustee usually should be an independent individual or institution. The general outcome is that the trustee could make no distributions, or they could even distribute the entire trust (subject to other duties). This will become important later when we discuss trust decanting.

Balancing Needs of Beneficiaries

While discretionary versus mandatory distribution powers seem simple by classification, these two powers reflect a tension inherent in most trusts. A trustee’s discretion has to take into account not just the needs of current beneficiaries, but also the needs of remainder beneficiaries. A trustee must objectively balance these competing needs. Current distributions, especially of principal, reduce principal available for future beneficiaries. Likewise, investment of principal in a way that emphasizes current income over growth reduces the amount of principal available to remainder beneficiaries under time value of money principles.

But, on the other hand, the limiting or withholding of current distributions, or investment that favors future growth over income, could also shift benefits from current beneficiaries to remainder beneficiaries. This could also hold true in a sprinkle power where beneficiaries from multiple classes, or generations, have the current right to receive income and/or principal.

Many trusts address this tension by adding conditions that limit the trustee’s discretion or duties to remainder beneficiaries or that stratify current beneficiaries. For example, in a credit shelter trust or marital trust, the needs of a surviving spouse limit the amounts that might remain for descendants of the settlor currently or at the surviving spouse’s death. These types of trusts may spell out the intent that the trustee emphasize the needs of the spousal beneficiary over the need to preserve principal for the descendants. (This can become extremely important in situations where the spouse is the trustee or a co-trustee of either such trust.)

Another example in this situation may be where descendants’ trusts are created, especially by family line. In such a case, you might have a trust under which a member of generation 2 is the primary beneficiary, but the children and descendants of that primary beneficiary are also given current rights to receive distributions along with a remainder benefit. In such a case, the trust may emphasize the needs of the current beneficiary over their descendants – again with the intent of limiting conflict if/when that primary beneficiary becomes trustee or co-trustee of their own trust.

As introduced above, where a trustee has full discretionary distribution powers (not limited by an ascertainable standard), as much as all of the trust income or principal could go to one beneficiary. It could even go into a new trust for some or all of the trust beneficiaries of the current trust. With this power, however, comes great responsibility, which makes it even more important to consider the trustee’s duties between current and remainder beneficiaries.

While this is more of a subject for later, state law may create solutions to this tension. For example, where there is a mandatory income distribution right, a trustee may be able to convert the trust into a total return unitrust – capping distributions at an amount of the current year’s value of the total trust, usually between 3% and 5%, first satisfied from trust income before dipping into principal.

Identification of Trustee

While the trustee role has traditionally been held by one person or institution, many trusts now bifurcate different functions of the trustee among different individuals or institutions. The common bifurcated trustee functions include investment, administrative/recordkeeping, and distribution. Given this modern approach, identifying the trustee of a trust itself may not be sufficient. Especially in states allowing for such a bifurcated role, the trustee holding distribution powers may be separate from the other trustee(s). Sometimes, there may even be a committee of trustees holding distribution powers.

Identification of not just “who” holds distribution powers, but also “who” can remove and replace a trustee with distribution powers, can also be extremely important. It is often the case that a beneficiary is a trustee or has the right to name themselves or a sympathetic party as a replacement trustee. In the worst case, a trustee’s distribution powers can be attributed to a beneficiary – both for tax and creditor protection purposes – in this situation. This risk can be mitigated by limiting any actual or “attributed” distribution powers to an ascertainable standard, and can be further strengthened through the use of a co-trustee or independent trustee. We will discuss specific requirements for independent trustees in a later article, but independent trustees are best thought of as individuals or institutions that are not related or subordinate to a settlor or the beneficiary according to the definition set forth in IRC Section 672(c).

Conclusion

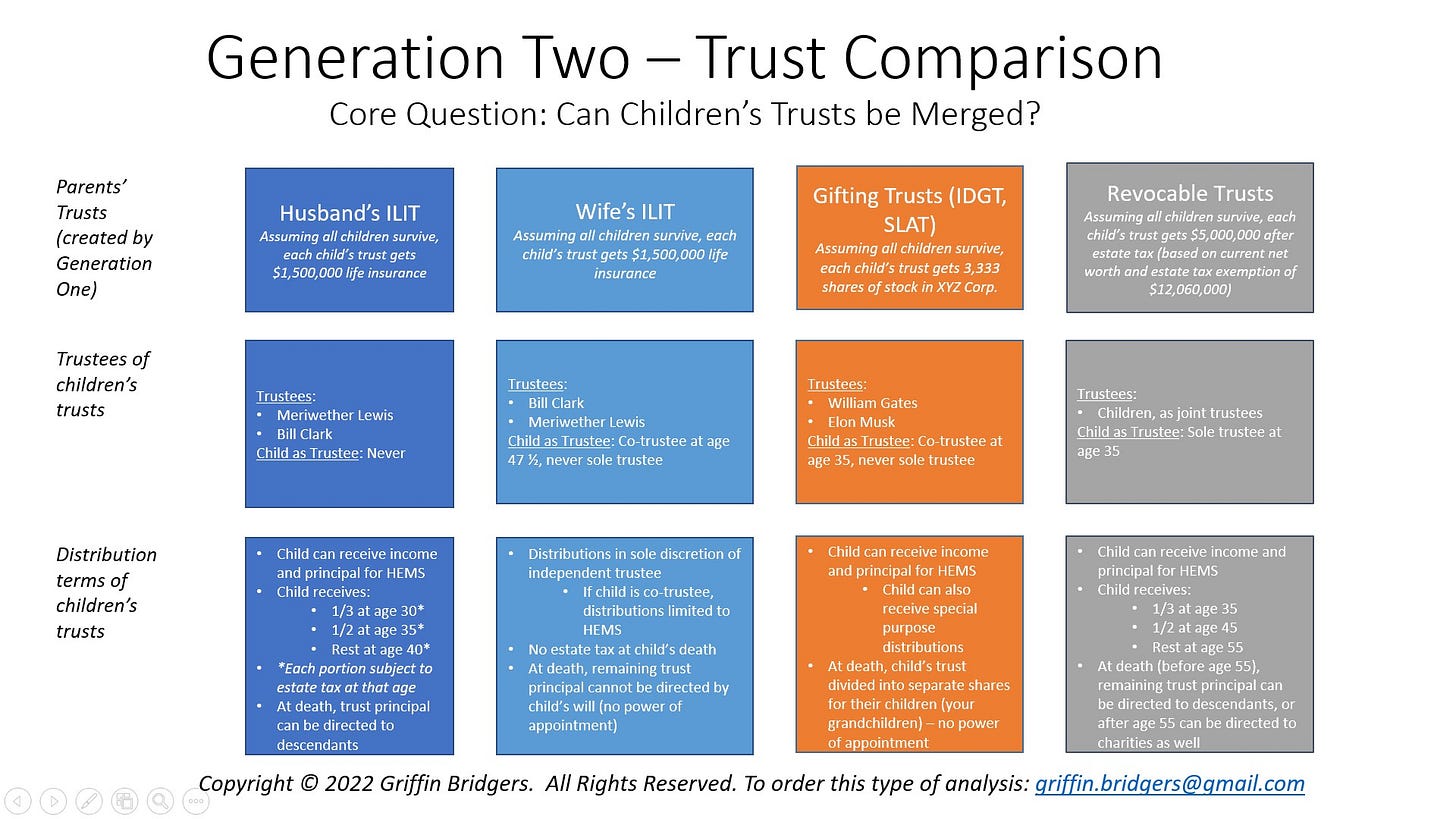

Classification of distribution powers can be extremely important for determining the type of trust, and the scope of a trustee’s duties. Differences in distribution powers also become important in comparing a beneficiary’s interests across multiple trusts.

Trustees may have a duty to balance their distribution powers not just within the trust they administer, but also across multiple trusts for the same beneficiary. Sensitivity to the tax and creditor protection elements of distribution powers is vital for trustees, attorneys, and advisors alike, and while this article does not address all of these tax and creditor protection risks, these are subjects we will cover at the top of the bell curve in this series.

[1] See, for example, Tennessee Code Annotated Section 35-15-103(10)(g), noting that use of mandatory distribution terms like “shall” may not create a mandatory distribution right if subsequently qualified by discretionary distribution language. While not cited by the statute, an example of such language may be “shall, in the trustee’s full and absolute discretion…”