What Are Descendants’ Trusts?

Starting with the end in mind in examining estate and trust distribution outcomes

This is a continuation of the series on everything you ever wanted to know about estate planning trusts. For an intro and index to this series, please click here. The linked article will have a series index that gets updated periodically as well, so please bookmark it.

Table of Contents

Framework

Over the last few articles in this series, I have introduced concepts that can be applied in the context of the trusts to be discussed herein. In fact, much of my focus has been on topics that have specific application to (what we will come to know as) descendants’ trusts. Powers of appointment are often an important element. Different perpetuities periods can apply to the various trusts created for descendants by parents or other family members. The tax and creditor protection mechanisms often relate to the trustee’s distribution powers, for reasons we will discuss in another article (or series of articles, because this subject becomes a state-specific and often judicially-driven moving target).

Intro

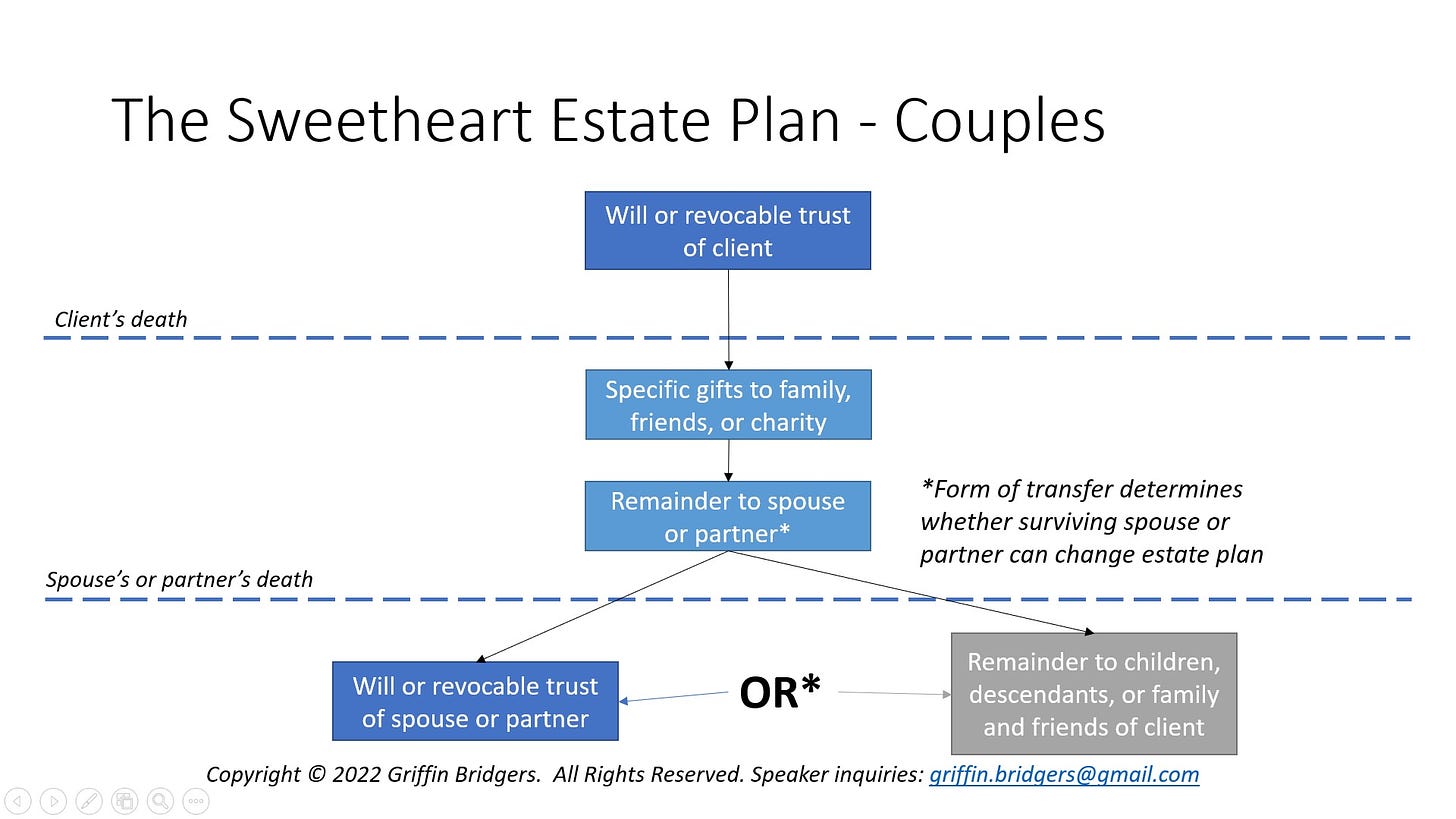

When working with clients on the structure of estate plans, I often like to start with the end in mind. In other words, where do you want the balance of your estate to ultimately go after taking into account spousal gifts, specific gifts, and tax-motivated transfers?

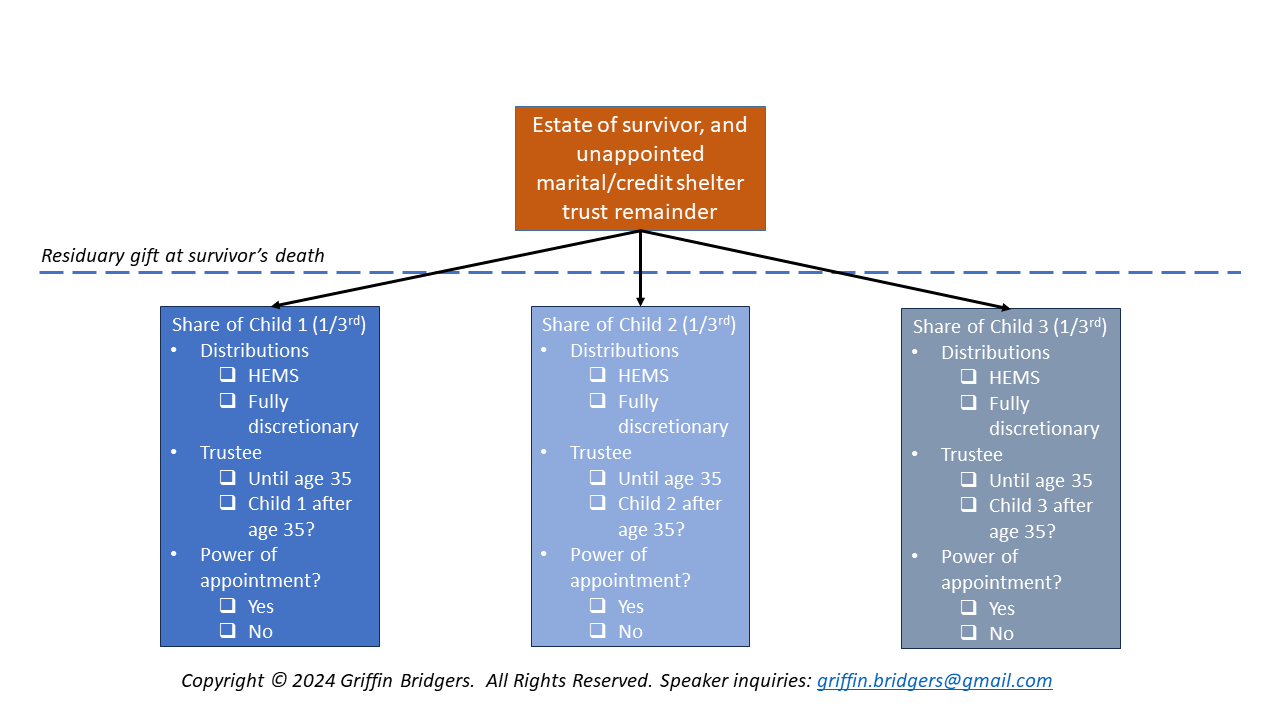

For married couples with children, the outcome is often that children will receive equal shares based on value of the estate. The calculation of equal shares may be subject to offsets for lifetime advancements or loans, but this is a subject for another time.

Over time, the complexion of these shares to be created for children has changed significantly. Long ago before I entered the practice of law (which may not actually seem like that long ago to some of you), it was standard to leave shares outright to children. These shares had no strings attached, and subject to rules around capacity to contract prior to the age of majority, this usually meant that children who reached adulthood had no strings attached to their inheritance.

Then, there was a period dominated by the tiered-distribution trust. This meant that the outright distribution of a share to a child was controlled by their age at the time of distribution. For children under a certain age at the time of creation of their share, they would receive tiered distributions (usually in one-third or one-half tranches) at universal “milestone” ages. For example, a child might receive one-third at age 25, one-half at age 30 (which was really another one-third of the original balance, plus one-half of the growth between ages 25-30), and the rest at age 35. For a period of time, most attorney-drafted documents contained this distribution pattern. (Some online document providers, and attorneys, still include this as a standard distribution scheme.)

Finally, we find ourselves in the current environment where asset protection and tax preservation has become increasingly important. To maximize this protection, while also exempting trust assets from future estate or GST taxes, the tiered distributions have been removed in many cases. Instead, shares for children and descendants are often held in either a lifetime trust, or a dynasty trust structure. For at least the lifetime of the inheritor generation, no outright distributions are guaranteed. Instead, a trustee controls the purse strings throughout the inheritor’s lifetime (with the option for the inheritor to control trustee choice). This type of trust structure is sometimes referred to as the “beneficiary-controlled trust.”

This beneficiary control is often found in two areas, but by no means does the trust have to be structured in this manner. One, the beneficiary may have the option to become a co-trustee or sole trustee of their own trust – often using the milestone ages described above for tiered distributions. (This may also take on the structure of the power to remove or replace trustees, or name co-trustees, at milestone ages.) Two, the beneficiary is often granted at least a testamentary power of appointment, and sometimes a lifetime power of appointment, to control the ultimate disposition of their trust.

Absent an exercise of this power of appointment, at the beneficiary’s death, their trust is usually divided into shares for their descendants – usually using a per stirpes distribution scheme, but sometimes instead using a per capita distribution scheme. If a beneficiary lacks descendants, their share may instead be added per stirpes (or per capita) to the existing shares or trusts for their siblings, and/or nieces and nephews. If a new share is created that is not added to an existing share, it may follow the prior beneficiary-controlled trust distribution scheme or, instead, follow the tiered distribution or outright distribution schemes.

Nomenclature, Source, and Importance

As we discussed with credit shelter trusts, there is no standard naming convention for the trusts to be created for a child or descendant. You may see these shares described as descendants’ trusts, residuary trusts, children’s trusts, or some similar term. Nonetheless, when reviewing a document, it is important to look to the residuary distribution scheme – often the contingent distribution (for a married couple’s estate plan) – to identify the structure of these trusts. (We will discuss review of estate plans in a separate series, as this is a rabbit hole in and of itself.)

As alluded to in prior articles linked above, these descendants’ trusts can be found in a variety of places. You may see them created as testamentary trusts under a will. You may see them created as subtrusts of a revocable trust at the death of a settlor. You may see them as subtrusts created from an existing, irrevocable credit shelter trust or marital trust. You may see them created in lifetime irrevocable trusts at the time of funding. And, as mentioned above, you may see them created as a division of upstream descendants’ trusts at the death of a parent or older generation – whether by the terms of the trust itself, or by the exercise of a power of appointment.

Regardless of the method of creation, being able to identify elements of the structure of descendants’ trusts can be important for a variety of reasons.

If you are assisting a beneficiary with their own estate or financial planning, analyzing their control elements (often trusteeship or powers of appointment) is a value-add.

If a beneficiary is going through a lawsuit or divorce, analysis of the creditor protection elements of their shares (again invoking beneficiary control) may be important. Expert witnesses may be needed to opine on the structure and classification of the trust from a property or tax law perspective.

If you are assisting a trustee or acting as trustee yourself, knowing the beneficiary and priority of distributions becomes important.

If you are placing or selling an investment on behalf of the trust, knowing the responsible parties, the differences from individual ownership, and even the ability (or lack thereof) to provide representations, warranties, guarantees and indemnification, can be important.

And, last but certainly not least, if you manage a business owned by a trust share, walking the tightrope between a beneficiary’s demands for business income versus the reinvestment of income into the business becomes extremely important.

Common Distribution Schemes

The trustee’s discretionary distribution powers often vary within descendants’ trusts. But, at the top of the bell curve, we can often build a layer cake of common outcomes and options.

Before diving in, however, one must identify the current and remainder beneficiaries. There is usually a child or descendant of the settlor who is the primary beneficiary of the trust, and their descendants will usually be remainder beneficiaries. Where descendants’ trusts can differ, however, is in the ability of the descendants of the primary beneficiary to receive current distributions. Sometimes, only the primary beneficiary may receive current distributions. Other times, both the primary beneficiary and their descendants are entitled to receive current distributions. This difference may have significance from a GST tax perspective, or simply be based on a settlor’s preference.

Sometimes, we might see a common trust for the immediate next generation – under which, for example, all children would be current beneficiaries until the youngest child reaches a certain age (like age 25) or, if earlier, graduates from college. Then, at that point, the common trust would be divided equally into separate descendants’ trusts for each child.

Regardless of whether the current beneficiaries consist just of the primary beneficiary, or also include the descendants of the primary beneficiary, the trustee will usually have the power to make distributions at least of income, and often of principal as well. These distributions will usually be limited by an ascertainable standard such as the health, education, maintenance, and support (HEMS) of the primary beneficiary. You may also see a limitation (for tax purposes) under which the trustee may not make distributions which discharge a legal support obligation, usually of the settlor and settlor’s spouse and sometimes of the primary beneficiary.

Layered in, you may also see a second distribution power reserved solely for an independent trustee. In this context, the independent trustee cannot be a beneficiary of the trust, nor can it be anybody who is related or subordinate to the settlor or a beneficiary. This trustee may have an expanded distribution power which disregards the ascertainable standard. As alluded to in the article on trustee distribution powers, this type of power is often considered a fully discretionary distribution power.

Beyond HEMS or fully discretionary distribution powers, additional guidelines may be found – either in the trust, or in a side letter from a settlor to the trustee. These guidelines may further define permissible distributions to include life milestones such as purchasing a home, starting a business, or paying for a wedding. These guidelines may also contain principles for withholding distributions if, for example, a beneficiary is underemployed, not maintaining a certain GPA, struggling with addiction, or is vulnerable to undue influence. These guidelines may also create certain priorities – looking to a beneficiary’s other resources (including employment income, scholarships, and/or health insurance) before making distributions, or prioritizing the needs of the primary beneficiary over the needs of their descendants (whether as current or remainder beneficiaries).

Trusteeeship

The challenge in creating descendants’ trusts is often the choice of trustee. Especially where dynasty trusts are involved, it is almost certain that the trust will outlive the trustee(s) to be selected by the settlor.

As mentioned above, this can partially be mitigated by giving the beneficiary some control over the trusteeship at a certain age. It is important to address control this in the trust because even in states following the Uniform Trust Code, the filling of a trustee vacancy may require unanimous consent of “qualified” beneficiaries or, in the absence of consent, court approval.[i] So, much like we started with the end in mind in planning for descendants’ trusts to begin with, stress-testing trustee vacancies (for existing trusts) in a situation where all named successors in the document are not able to serve can be a good starting point. From there, we can work backwards to determine what control a beneficiary may have.

Going the other way, if we are in the design phase for a document yet to be drafted, we often start with an option for each primary beneficiary to become a co-trustee or sole trustee of their own separate trust at a certain age. I usually see age 35 used here as a starting point, but the settlor can choose any age they want starting at the age of majority. Until that age, selection of a separate trustee (and successors) becomes an important consideration. Starting at a certain age before the beneficiary takes over, there could even be an apprenticeship where the primary beneficiary (as co-trustee or otherwise) learns about the management and investment of their trust from the acting primary trustee.

As noted in a prior article, a beneficiary as trustee may have a general power of appointment for federal estate/gift/GST tax purposes if their distribution powers are not limited by an ascertainable standard. Under the principles of Rev. Rul. 95-58, this may extend to a beneficiary’s powers to remove an existing trustee and name themselves, or a sympathetic (i.e., related or subordinate) party as successor trustee. So, if the beneficiary is or may be trustee or can control/influence their selected trustee, cross-referencing the existence of an ascertainable standard limitation (if not already assumed under state law) is extremely important.

Beyond tax, though, we must be concerned with the creditor protection limitations. Unlike federal tax principles, these limitations can vary by state. While some principles between tax and creditor protection are similar, they are not universal. In some states, a beneficiary acting as a co-trustee or sole trustee may not be treated any differently from a typical trustee as fiduciary duties are considered to override any self-interest. But, other states may reach the opposite conclusion. At the very least, it can be helpful to avoid forcing the beneficiary to become a trustee. Using language such as “may” versus “shall,” while appearing petty on its face, can be extremely important when we make this distinction. So, if the trust says a beneficiary “shall” become trustee at a certain age, this may not create as much protection as a trust that says a beneficiary “may” become trustee.

There are several other concerns, including the role of directed trustees, trust advisors/protectors, and the succession of trustees beyond the immediate next generation to consider. But, by establishing a baseline of beneficiary control over trusteeship, we can create enough flexibility to limit the risk of court interference.

Creditor Protection

As a preface, this is not intended to be a comprehensive discussion on asset and creditor protection. Lots of factors come into play which are not covered here, and each principle is highly state-specific. The picture I paint in the following paragraphs is overly-simplified, and designed to give you a baseline average to work from.

But, to set the stage, the advantage of descendants’ trusts over outright or tiered distributions is the protection of a beneficiary’s inherited share from claims against them by creditors. These claims could include those of judgment creditors, or even claims related to a divorce (which get into discussions of separate property versus marital/community property which we will later address).

In many states, a beneficial interest in a trust is treated as personal property as a default. The outcome is that, absent other restrictions, a beneficiary of a trust can transfer their interest in the trust. This could extend to the claim of a creditor against the beneficiary, who can force the beneficiary to transfer their trust interest in satisfaction of a claim.

To avoid this outcome, trusts entered into for estate planning purposes almost always include a restriction on alienation, usually known as a “spendthrift” clause. In short, this type of clause prevents a beneficiary from transferring their interest in the trust, whether voluntarily or involuntarily. This clause also prevents a beneficiary from pledging or encumbering their interest in the trust.

Note that states usually recognize spendthrift clauses, but not uniformly. The point on which most states vary is the identification of exception creditors/claims (usually from a public policy perspective). Certain types of claims against a beneficiary, such as claims for unpaid child support, may not be protected by a spendthrift clause depending on the state.

In addition to spendthrift clauses, powers of appointment (especially lifetime powers of appointment) may affect the creditor protection afforded to a beneficiary. Usually, a creditor cannot compel the exercise of a testamentary power of appointment – even if it is a general power of appointment exercisable in favor of a creditor as an appointee. But, in some states, lifetime powers of appointment (especially general powers of appointment) may not be granted the same protection. Crummey powers are often protected, but broader lifetime general powers of appointment may not be.

In this vein, however, fiduciary duties can add an additional layer of protection to prevent a creditor from compelling a beneficiary to exercise a lifetime general power of appointment. In the article on powers of appointment, I alluded to the fact that trustee distribution powers are technically classified as lifetime powers of appointment. Where a beneficiary is also a trustee, fiduciary duties may or may not prevent creditors from treating their distribution powers as enforceable lifetime powers of appointment depending on the state. These nuances will be left for later articles.

The question then becomes whether the beneficiary is guaranteed to receive any distribution whatsoever. Once property has been distributed by a trustee, it is no longer protected by the trust’s spendthrift clause. At that point, a creditor could execute on the distributed property to enforce a judgment or property award. But, if distributions are guaranteed – such as mandatory distributions of income, or the tiered one-third distributions described above at milestone ages – a creditor could garnish such future income distributions or execute on its claim at the time of a guaranteed principal distribution. This is why the imposition of trustee discretion is often preferred.

In this vein, the presence of an ascertainable standard usually does not create a guaranteed distribution. But, at the same time, a beneficiary whose needs are not met elsewhere could have an enforceable distribution right depending on the state. Such an enforceable distribution right could, depending on the state (and even the court), be considered a power of appointment the exercise of which could be compelled by a creditor even where a trustee’s discretion is limited to an ascertainable standard.

Finally, I would be remiss if I did not mention the issue of self-settled trusts. The protections described above may go away in situations where a beneficiary has contributed their own property to a trust, thus wearing both hats of settlor and beneficiary. This self-funding creates what is known as a “self-settled” trust. Some states treat self-settled trusts as void against claims against the settlor/beneficiary by present creditors, and sometimes future creditors. When counseling clients, I often advise that “the toothpaste cannot be put back into the tube” with respect to descendants’ trusts. In other words, once a beneficiary takes a distribution, the distribution cannot be returned to the trust.

This prohibition against self-settled trusts is not the norm for all states, however. Some states allow for the creation of a self-settled trust, often called a domestic asset protection trust (or DAPT for short). A DAPT may extend the protection of a trust’s spendthrift clause to a settlor/beneficiary, subject to certain requirements and exception creditors/claims. At the very least, a trustee (other than the beneficiary) in the state recognizing the DAPT may be required. (We will discuss state situs in another set of articles.) Some states require the settlor/beneficiary to execute an affidavit of solvency for each funding of a DAPT. And, in most if not all states, fraudulent or voidable transfer laws apply at the time of each transfer to allow creditors to avoid certain transfers occurring within a certain period of time before a claim – often 2-5 years depending on the state (not just of DAPT situs but settlor’s residency) and/or type of claim. The voidability of a claim by a creditor may consider whether (1) a transfer to a DAPT rendered a settlor/beneficiary insolvent with respect to present or foreseeable creditors, or (2) a transfer was made with the intent to defraud future creditors.

Conclusion

The design elements and options for descendants’ trusts are numerous. Nonetheless, there is a tension between past and present for the “norm” in estate planning. Individuals engaging in the estate planning process also encounter their own tension between dead-hand control and letting go of the risks associated with outright ownership of an inheritance. Some of these risks, such as creditor access and tax exposure, may persist even for beneficiaries who would otherwise be prudent with the management and preservation of their inheritance. But, outside of tax and creditor risks, the descendants trust creates a way to protect the beneficiary from themselves during their least “mature” years while also creating the option to pass control (but not ownership) to them at some magic age or milestone of maturity.

Coming up, we will next examine some of the division and formula language that can be used for descendants’ trusts – including GST tax concerns, funding, advancements, tax apportionment, and lapses.

[i] UTC 704(c).